TRACED BACK HERE

A man tries to unshroud the mystery of his parents and his past in Ty Landers’ short story, set in the American South. Illustration by Bartosz Kosowski.

We got out of the car and walked up a little gravel driveway that led to an overgrown foundation where a house had been.

‘Son,’ my father said, ‘this is my hometown.’

He paused and surveyed the small plot of land that had been mostly reclaimed by the scrub brush that surrounded it. There were some railroad tracks thirty or forty yards from where we were standing and I could imagine pots and pans rattling in any house unfortunate enough to be situated in that spot.

‘Everything that I can’t explain about myself…everything that makes me the way I am…can be traced back here…to this house.’

It was quiet. We had been on the road for a long time and I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t know if I should say anything at all or if this was one of those times when silence said more than filling an uncomfortable space with nervous words.

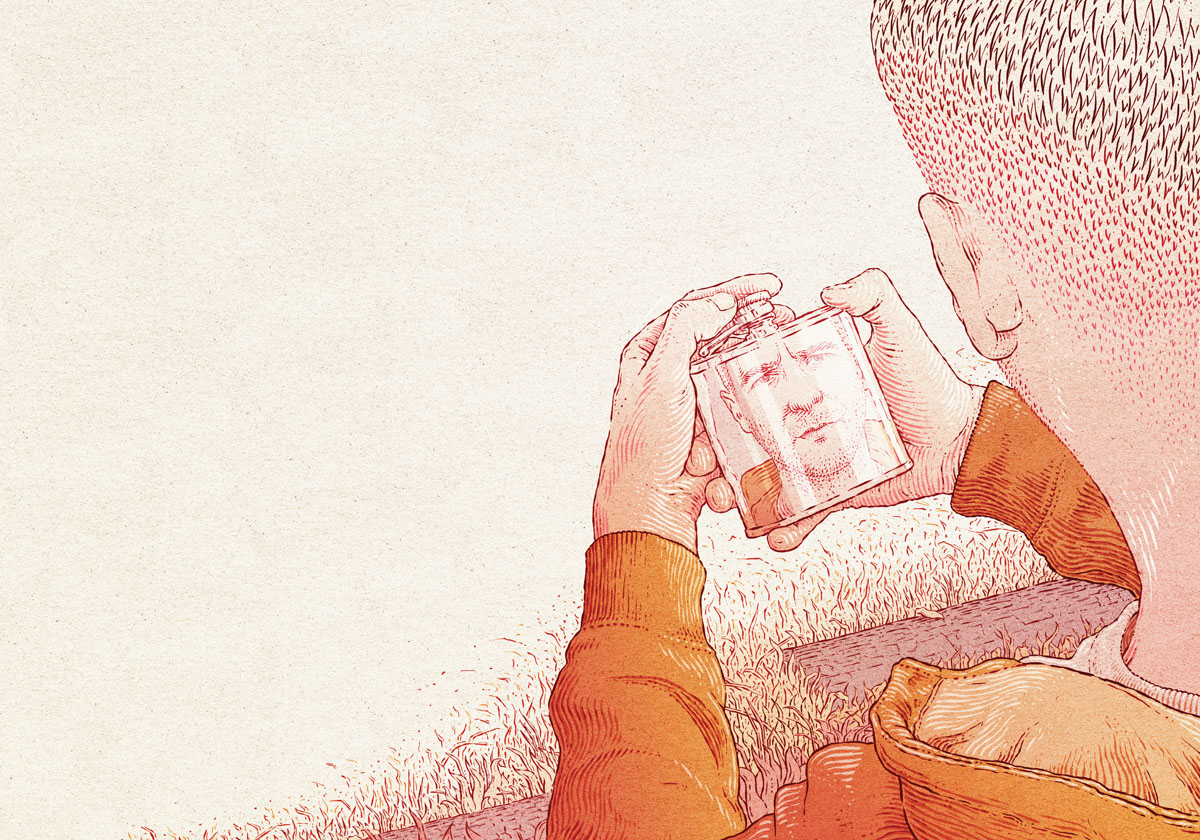

My father started to cry. It was the first time I had ever seen him cry and it scared me. I had seen his dark side. I had seen him mean before, and drunk plenty of times. In those days when I saw his ancient silver flask peeking out of the pocket of his work shirt I knew I would probably be sleeping in the car or the shed that night while he stalked around the house looking for something to break or scream at.

I didn’t question these parts of him or the things he did, didn’t question why we moved around so much – Wisconsin, Illinois, Ohio, Tennessee, and now Alabama. I didn’t even question why we changed our names every few years, why we had no family, or why I didn’t even know my mother’s name. My father wasn’t a communicator. He wasn’t the type of man who let you in or filled in the blank spaces.

I couldn’t look at him. I thought I might turn to stone if I did, and hearing him try to contain the sobbing made me want to leave that place, to get back on the road and start trying to forget any of this had ever happened.

Summer bugs, unknown to me, purred and snapped in the tall grass all around us. Sweat poured down my back in runnels and my clothes were tacky against my skin. He gathered himself but continued to breathe heavily. He put his weathered hand on the back of my neck while his chest hitched and eventually settled into a steady rhythm.

We got back into the car, pulled out of the little gravel driveway, and picked up the highway after weaving in and out of roads I had never seen before and would never find again.

We drove into a sunset that looked like a watercolor painting by a small child with no concept of subtlety; a riot of pinks and oranges that fused together in a gaudy show that pulled us west. After some time my father broke the silence. ‘They got a rocket in Huntsville, the real deal, one of them that they sent to the moon back in the sixties.’

‘Is that right?’ I asked, looking out of the window at the passing countryside.

‘Oh yeah, once them Nazi scientists realized they were licked and was going to lose the war, they gave themselves up to our boys. The army snatched up as many of those egg heads as they could with all their plans, and schematics and such, then shipped them over here to build rockets for us.’ He readjusted his hat. ‘That’s what put Huntsville on the map. I think you’re really going to like it.’

‘If they were Nazi’s, then how come they didn’t get in trouble after the war for the things that went on in them camps?’ I asked.

My father thought about this, one hand on the steering wheel and the other rubbing the stubble on his chin. ‘Son, sometimes your potential outweighs your misdeeds.’

The sun went down and the stars came out. We drove on without saying much else. I thought my father might talk about my mother, or maybe tell me about my grandparents for the first time, or anything about where we came from. But he didn’t. He seemed to have moved on to Nazi’s, spaceflight, and Wernher von Braun. I got the feeling that if he was ever going to talk, it would have been at the end of that little gravel driveway, mired in all that grass and a symphony of bug songs, peering out over the wreck of a house that he considered the genesis point of his peculiarity.

That night I had a dream. I was walking down a long hallway in a castle somewhere and the hallway kept pushing me deeper and deeper into the interior of that strange place. Along the corridor there were these huge Nazi flags billowing in sinister dream light. They were the deepest red I had ever seen with their dark black swastikas standing out in their menacing white circles. I walked until I came to a huge circular room. The walls were covered with the same ominous red flags from the hallway and they stretched up into darkness. The ceiling and roof were gone and I could see an endless sea of stars. My father was there, in a brown uniform expertly tailored to his slender frame, and he held a baby in his arms. In the center of the room there was a little rocket that looked like it should be sitting out in front of a grocery store, giving jerky rides to kids for a quarter a pop. My father placed the baby gently into the little rocket and then stood there silently watching it. It reminded me of the scene in Superman where Marlon Brando put baby Superman into a sharp crystal pod and blasted him to safety in Kansas before his home planet was destroyed. It was just like that except Superman’s dad was my father and also, a Nazi.

In my dream the little rocket blasted off and my father vanished in rocket smoke, flame, and the eerie green dungeon light of the castle. The rocket peeled off into the sky in this drippy orange arch and I was able to follow after it, chasing it through the slipstream. Then I woke up. I never caught it and I never knew exactly where it was going. Maybe Kansas, or some other backwater – hopefully somewhere safe.

My father started a job in Huntsville doing maintenance at a tire plant and we never talked about the trip to his hometown again. I finished high school there and we settled into the first period of stability that I could remember. I made some friends, dated a few girls here and there, but I could never really get into the habit of letting people get close. The urge to change my name and move to a new town came over me regularly and I assumed that was either a hereditary trait my father passed down to me, or something I learned from our nomadic lifestyle.

I remember asking him once why we had moved around so much when I was younger. I expected him to say something about work being difficult to find or something along those lines, but he just sat in his old chair staring at the fire over a glass of bourbon and half melted ice and said ‘restlessness’. I didn’t press the issue any further.

He had a heart attack when he was sixty and died instantly, hanging halfway out of a machine that he had probably worked on a thousand times. The funeral was simple and cheap because we didn’t have any family that I was aware of, and my father’s only acquaintances were the guys he worked with, the men who worked at the liquor store he always went to, and me. I didn’t even bother putting an obituary in the paper. I sat down to write one but realized I didn’t know enough about him to make it worth the effort.

Cleaning out his house was easy. I called the Salvation Army to come and take everything they could fit onto the truck. While going through my father’s bedroom, I found a shoebox in his closet where he kept his important papers. Mixed in with his social security card and his ancient birth certificate – different names on both but names I was familiar with – I found a picture of a basketball team. Blue Pond High School, Blue Pond, Alabama, Class of ’68, was written on the back in faded pencil. On the front, kneeling down in the first row with a crew cut, but still looking very much like me, was my father. There was no name on the picture but I would have known him as easily as I would have known my own face. I took the box and the picture with me and looked at it for a long time that night. It was somehow comforting to know that he had been young once, I had proof of that, and I knew the name of the town where we had spent that brief and awkward summer afternoon when he had almost opened up his personal vault of secrets.

The photo sat on my kitchen table and I stopped to look at it every time I passed it for about two weeks after he died. It drew me in time after time as I did little chores around the house. I couldn’t get over how young he looked and how much I looked like him, or how much he looked like me. It was nice to have a glimpse into the past he never spoke about, to have some insight, and it left me wanting more.

So, I got up one morning, grabbed the photo of my father, and punched Blue Pond, Alabama into the GPS on my phone. I also grabbed the flask that my father had carried with him the entire time I had known him; one of the only items of his I had kept besides the picture. I filled it with bourbon in his honor, and drove south into the deep green countryside.

I arrived in my father’s hometown at about midday. The better part of three hours were spent driving aimlessly around, hoping some landmark would stand out and jog my memory enough to take me back to the empty lot my father had placed so much importance on. I didn’t know what I hoped to find when I got there, I just felt an overwhelming urge to get there. Something was pulling me back and I had to see it again.

There was an old walk up burger stand called Dairy Dream at a four-way stop at the end of the main street that ran through town. It was the first landmark I remembered seeing from our trip because it had a sign depicting a gorgeous blonde genie emerging from a lamp, cheeseburger in one hand and a soft serve ice cream cone in the other.

There was a gas station beside the burger stand and I showed the photo to the lady working behind the counter, but she had never seen my father and didn’t remember ever hearing his name. I sat on the hood of my car outside the Dairy Dream and drank from the flask my father had carried with him for years, trying to get my bearings. When I ran out of realistic solutions, I decided to let fate sort it out. I placed the flask on the hood of the car, spun it like I was playing a game of spin the bottle, and decided I would go in whatever direction it pointed. It came to rest pointing south down the road that headed away from the tiny oasis of civilization there at the four-way stop. It felt right. I can’t explain how or why or what force was behind it, but I knew it was the way I needed to go. I repeated the trick several times over the next forty-five minutes or so. Every time I would come to a turn, I got out of the car and spun my father’s flask on the hood without questioning the logic behind it.

I drove down a long country road, surrounded on all sides by farmland that was broken up by sporadic stands of trees here and there. The road ran parallel to a set of railroad tracks and upon seeing them, I knew I was headed in the right direction. Despite a history of skepticism regarding supernatural intervention, I knew that my father’s flask had led me there. Eventually, I found myself pulling into the faint remains of an old gravel driveway that led up to the foundation of the old house, now firmly buried beneath the wild brush that ran up to the railroad tracks.

There was a house across the street that hadn’t been there when my father and I had visited years before. An old man leaned against a fencepost while having a heated conversation with a big black bull standing in a pasture, shoulder deep in yellow wildflowers. He stopped talking to the bull, watched me pull into the driveway, and then resumed berating the huge animal.

I got out of the car and stood there in a daze. I couldn’t believe I had found it, I couldn’t believe the flask had brought me back. Now that I had found it, I didn’t know what to do there. The flask was still in my hand. I had been holding it like a talisman of some sort since deciding to surrender my fate to it, and I decided that all I could do was make a toast. I held the flask up to the overgrown foundation of the house and to the railroad tracks beyond it. ‘This is for you Dad, thanks for bringing me back. I wish I had been able to…I wish I had known more…’ I paused and couldn’t think how to finish. ‘I just wish I had known you better.’ I tipped the flask back and enjoyed the burn down my throat.

‘You lost?’ the old man said walking across the road, and shaking me out of my daze.

‘Lost?’ I said. ‘Kind of, just making a pit stop.’ I shook the flask at him.

‘Son, you sound like a man after my own heart.’

I offered him the flask and he took it, clapping me on the back and showing a huge friendly grin.

‘We don’t get many day drinkers out here.’ He took a long pull from the flask and then shook his head from side to side like a dog just emerging from a pond.

‘Woo! What is that…kerosene?’

‘Sorry,’ I said laughing, ‘It’s my Dad’s bourbon and it’s a bit rough.’

‘Well, it’s better than nothing. My wife found the bottle I kept in the shed and I ain’t had the balls to replace it yet.’ He shook his head again and passed the flask back to me. ‘Holy Roller that wife of mine, she does not abide the bottle.’

‘Is this your land? I didn’t mean to trespass.’

‘Nah, this ain’t my land, belongs to the Shields family. They own about a thousand acres, this here is the ass end of it. Hell, they probably forgot they own this.’ He leaned against my car.

‘Do you know anything about the people that lived here?’ I asked, handing him the flask again.

‘Well, this house burned to the ground, awful really, I guess it was the late seventies, early eighties. There was a young couple that lived here, had a baby. House caught fire, some kind of gas line thing or hot water heater…pilot light maybe went out and the old boy tried to relight it.’ The old man hit the flask again and looked at the ground, sucking air between his teeth to help with the bite of the bourbon.

‘Was anybody in the house, anybody get hurt?’ I asked.

The old man looked around at the fields that were surrounding them. ‘You know, back then, there wasn’t much around here,’ he laughed a little, ‘not that there’s much out here now but back then there was even less out here and I guess the fire burned for a long time before anybody…the fire department or whoever…could get out here.’ He handed the flask back to me and then hooked his thumbs in the straps of his overalls. ‘They found enough of the girl to know it was her but they never found that old boy or that baby.’ He made a sympathetic grunting sound, ‘breaks your heart don’t it?’

We sat in silence for a little while as the wind pushed itself around in the treetops.

‘What’s your interest in this place?’ he asked after some time. ‘If you’re thinking about buying out here or getting into farming I’d like to talk you out of it.’ He laughed his good-natured laugh but my mind was already a million miles away.

I had a hard time finding the words. Hundreds of questions swam around in my head and I wanted to sit down. I thought about my dream. The castle, the baby in the rocket, and watching my father disintegrate under a blanket of smoke and flames. I thought about the number of times that we had moved for no reason and how desensitized I had become to assuming a new name and a new identity.

‘What’s my interest in this place?’ I asked the old man absently. ‘I think that…everything I can’t explain about myself…everything that makes me the way I am…can be traced back here.’

To ensure that you never miss a future issue of the print magazine, subscribe from just £24 for 4 issues.