AUTUMN PLUNDER

A selfless villager finds her annual act of kindness is at risk of being misconstrued in Lucy Brown’s short story. Illustration by Zoë van Dijk.

There never was a horse chestnut tree in my garden. Still, the children came, year after year, leaving with pockets full. I had tea with their mothers on the patio, cooing as the little ones tromped through the leaves and occasionally came up with a prize. Autumn became my favourite season, those few weeks of bustle recompensing me for the rest of my solitary existence. Then, the leaves shrivelled into a brown sludge that eventually slithered into the pond. The fish hid, the birds stilled, and that was my excitement spent until spring, when the tree began its hardy rebirth.

But there never was a horse chestnut tree at the bottom of my garden. It was an oak.

People didn’t look up, that was their error. They didn’t study the tree so they didn’t question the miraculous conception, nor the excessive number of yearly births. If they had colluded, perhaps I would have been discovered, but it wasn’t that kind of village anymore. Since the school had closed, the mothers had stopped communicating, seeing each other as competitors. The elder generation died or kept themselves above the fray. I was neither a young mother nor an elderly resident, not even a long-term one, so there was no one to tell tales. Until now, there had been no danger of discovery.

It had started simply enough. Many of the horse chestnut trees around these parts lined the roads. That would have been fine were the roads thick enough to accommodate pavements, but they weren’t. Cars pelted through the village, paying no mind to the safety warnings. Only a parent completely blasé about their child’s safety would risk foraging at the roadside, and I’d only met a few of those in my time. The rest of the trees seemed to be in back gardens. Not the gardens of the young mothers, you understand; no, they didn’t have room to swing a rat, let alone a cat. They used the village green for all recreational activities, where some enterprising parish councilman had long ago decided to hack down the trees, not least because grass was easier to maintain than sprouting wood with an agenda of its own. That left the remainder of the coveted inner-village trees hidden away in the gardens of cantankerous ‘originals’ who hated the infiltration of the new developments and would sooner let the children get run over at the roadside than share their sanctuaries.

I’d seen the state of affairs when I moved in and I’d wanted to help. The lack of a horse chestnut tree in my garden was a hindrance, it’s true, but only a minor one. It took planning, diligence and, most of all, determination.

So I rose as soon as dawn broke. Bundled up in dark clothing, pockets stuffed with plastic carrier bags, I hastened to the roadside. The odd car zoomed by, but I heard them and flattened myself into the hedge or against the trunk of a tree. When I’d collected last night’s debris, I hurried home. The next part took skill. I couldn’t just toss them haphazardly amongst the oak’s leaves. No, the job was worth doing properly. Split casings had to be married up with similar-sized conkers and half-buried under crunchy leaves or rolled away for that added frisson of excitement. All this had to be done under the cover of gloom, before my neighbours were likely to see.

Until this year, it had worked. Then, towards the end of July, I’d made the horrific discovery: root rot. It was as ugly as it sounded. At the very moment my leaves should’ve been green and luscious, they were yellowing, fluttering to the ground like flambéed post-it notes. The canopy above, once impenetrable, was shot through with cannonballs. The worst offenders by far, though, were the new roots protruding like buffet tables from the trunk of the tree. The pus seeping from them ate into my heart.

What could I do? I looked it up on the internet and learned the tree would have to come down. I dithered throughout August, unable to grasp the nettle that would consign me to the footnotes of village history — the woman who used to let the children collect the conkers that fell in her garden. It may have been different had I a year to acclimatise myself to the alteration in status, but two months was no time at all. So, I hesitated until it was too late to stem the catastrophe.

The tree was standing; the children would expect conkers for their pockets, and that’s what they were going to get. I’d indulged in subterfuge to satisfy them for a decade; I could surely facilitate a little more to prolong this pleasure of mine for one more season.

It was all a matter of preparation. This year, I started much earlier. It was leaves I collected under the lightening skies, dragging bags full back to stack around the trunk and its protruding roots. They mulched up quickly, staining the ground but offering little in the way of protection. When I surveyed the scene from afar it looked convincing enough, but some parents weren’t content to survey their youngsters from a distance. I had to change tack.

I drove fifty miles to a garden centre and purchased thirty bags of compost. Under cover of darkness, as August faded away, I created an extra layer of ground above the bulging roots that petered off somewhere along the lawn. It didn’t look exactly natural, but I’d been fooling these people with an oak tree for years — I couldn’t start crediting them with sharp wits now. Over the compost, I peppered leaves, a sprinkling every day that eventually appeared passable. Then the annual conker collection began in earnest. I baked cakes, stockpiled sweets and waited for the first knock at the door.

It was an old customer who dropped by first: Mrs Dupree and her nine-year-old daughter, Angelica. I’d been welcoming her to my garden for years now and she was a favourite. Usually, I was happy to spend time listening to her chattering, polite child that she was, but this time I was only half-listening. My attention was devoted to the ground, her interaction with it, the way it looked when her hands delved into the leaves and came up with a conker.

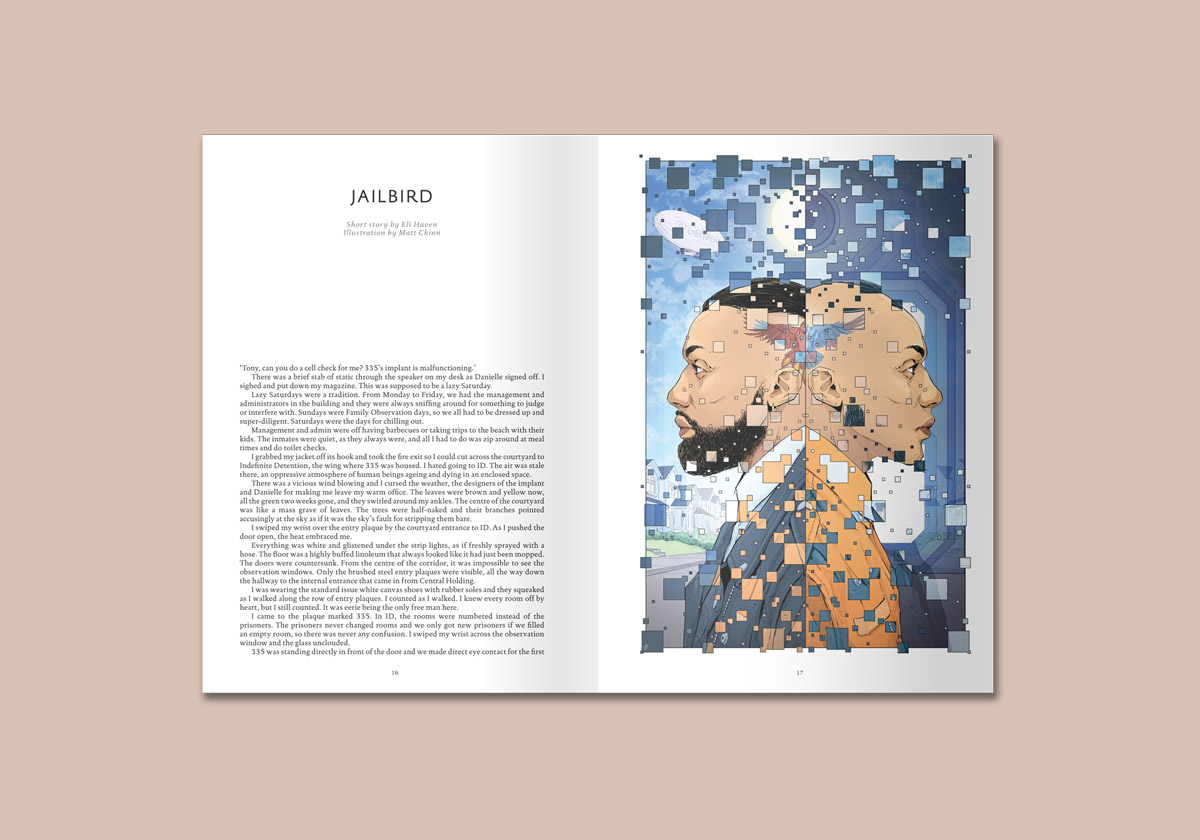

When the ordeal was over, I felt better. My decrepit tree, dying even as I watched, had passed one test. There was nothing to suggest it wouldn’t survive them all. After that, I settled a little. I enjoyed my hostess role, enjoyed the exhaustion of my early-morning jaunts to the roadside. We were perilously close to our daring escape, the tree and I, when disaster appeared in the form of Ms Foxton.

Ms Foxton and her small son Angus were recent patrons of one year standing. She was the type I endured in order to welcome the rest. Angus was a sickly boy, no nursery school for him, but long days fussed over by his mother instead, leaving him with the social skills of a squirrel. I’d acknowledged last year, while watching a grey-tailed friend play chicken with another of my visitors, that the comparison was perhaps an insult to the squirrel family.

The mother was no better. She kept me at arm’s length, emphasising the ‘Ms’ of her name and crinkling her nose if I sissed instead of zizzed. All the rest were ‘call me Pam’ types, insistent on first-name terms, but not Ms Foxton. She treated me like a public service, my cakes like an inferior version of those she bought at Waitrose. I would’ve gladly turned her away but I couldn’t afford to arouse suspicion.

From the moment Angus romped into my garden, I was on edge. Many mothers hung back with their cup of tea, but not Ms Foxton. Angus cried if he was deprived of her company for a few minutes and she, of course, indulged him to the letter. So, together, they approached the tree and I held my breath. To my relief, she didn’t have eyes for anything but him and they passed half an hour hunting through the leaves together. I prowled the patio, doing my best to keep an eye on them while pretending to tend my potted plants. Until she gathered him up to go, I honestly thought I’d gotten away with it.

He threw a tantrum. He wanted to stay, he wanted more conkers. I knew full well that they had the lion’s share of today’s haul in her bag but I kept quiet, mindful that a word from me would merely compel her to stay and be an inconvenience.

Her response to his tantrum was pitiful. She didn’t reprimand him, either for being naughty or greedy. No, she pandered to him and said he could go back to the tree – and back he went. He ran like a demon and, in spite of his mother’s entreaty, slipped head first into the leaves, his skull breaking his fall.

The garden was silent for a terrifying few seconds then his scream shattered it. Birds fled from the living trees, squawking to each other in indignation as they zoomed away. Ms Foxton leapt forward, her tights plopping into mud as she kneeled beside him. She touched his head, murmuring, begging, while he bellowed his misery and flailed about like an otter. Then Ms Foxton did what I was praying she wouldn’t — she started scrabbling at the leaves around his head.

I moved forward. ‘Mrs – Ms Foxton, would you like me to help you get him inside? I could –’

‘Don’t you touch him,’ she interrupted, then her search came to an abrupt halt as she reached the protruding root. Her eyes swept up the tree, taking in the browning trunk, the cracked branches and the dearth of canopy foliage. ‘It’s dead,’ she murmured. ‘The tree’s dead.’

Her horrified eyes swivelled to me, even while Angus howled beside her. She was sizing me up as a crackpot, as a paedophile, and jumping to conclusions. With someone else, throwing myself on their mercy might’ve worked, but not Ms Foxton. The horror was gradually replaced with the satisfaction of power and she finally hoisted her screaming son up.

‘The whole village will know about you,’ she spat as she carried Angus to the side gate. ‘And the police. You just wait, you freak.’

My body took that as a direct order. Even after she slammed the gate, I stood motionless, gazing at the offending symptoms of root rot and wondering where I’d made the wrong turn. It would all come out now; the oak tree, the dawn collections, the recent leaf-foraging expeditions and compost mountain. Was any of that against the law? I hadn’t charged for entry, I hadn’t even advertised. It was a verbal understanding, but if that was based on deception then was it a crime? For some reason, I’d never thought much about it.

Root rot. Why root rot? And why now?

‘Mrs Connolley?’

I didn’t know how many times the voice had repeated itself before it permeated my preoccupied mind. But when it filtered through, I jumped out of my skin, thinking it was the police already, or perhaps villagers with pitchforks. Turning, I found my neighbour, Mrs Hoskins, leaning heavily on her walking stick and swaying slightly. I must have been lost for quite some time for her to make it this far into my garden.

I tried to smile. ‘Oh, Mrs Hoskins. Is it the toilet again or another fuse?’

‘Are you all right, pet?’ she asked.

‘Oh, I…’ My eyes were still fixed on the tree, the damn tree.

‘Is it rotted through?’ she questioned, waving her stick at the trunk.

I flinched. ‘It’ll have to come down.’

‘And that Mrs-Smarmy-Whatsherface — what did she have to say about it all?’

My brain was slow to unfog but then I stared at her. ‘Ms Foxton, you mean?’

‘Aye, that one. Only reason she calls herself ‘Ms’ is because her husband’s having it away with thingymabob from the farm. Did you know?’

I shook my head.

‘No, no, you’re out of the loop. Anyway, don’t be fretting on about her. Whatever threats she’s made, she’s a bit short on friendly folk in this village. I doubt they’ll last the year out round here.’

This new information baffled me. Mrs Hoskins knew more about all the goings-on than she had a right to. An icy feeling settled in my stomach. What else did Mrs Hoskins know?

As if following my train of thought, she tapped her stick against the tree trunk. ‘Nice thing you’ve been doing for them kiddies. Keeps them safe, keeps their parents quiet. Lot of work for you though, pet,’ she added.

‘I don’t mind it. Well, I didn’t,’ I corrected. ‘It’s over now. Does everyone know?’

She cackled. ‘Not any of them halfwits you’ve been letting loose, don’t be worrying about that. How they expect their kiddies to grow up with half a head on their shoulders is beyond me. They don’t look up, do they? Or, if they do, they’re so daft that it makes no difference.’

I burst out laughing. The few birds that had ventured back following Ms Foxton’s outburst squawked and scattered again.

When I could breathe again, I asked, ‘Did nobody think to tell them?’

A wicked smile slid across her wrinkled features. ‘Well, pet, we thought about it. Then we thought better of it. Come on, lass, do you want a cuppa? I’ve got Martha and Jean coming round, we can have a natter.’

I took one last look at the decaying tree then squeezed her outstretched hand. ‘That’d be grand, Mrs Hoskins.’