HOME IS WHERE WE ARE

Ethan Chapman’s short story explores a family’s attempt to come to terms with abduction and the construction of a life in its wake. Illustrated by Joe Wilson.

I was sitting in the garden with my sister when a van took her away. I looked up and she was there. I looked down, distracted by something, something important. When I looked up again, the scenery had changed. There was a shadow stretching across the grass and I watched as a van door opened, the interior darker than shadow. I looked around for my sister and somehow she was by the van, a man’s arm pulling her inside. I saw my sister’s face look out at me, firstly with curiosity and then, when the door started to close, with terror. I watched all this – the van going away, exhaust fumes circling around the road, emptiness – and did nothing. It didn’t occur to me to do anything. It all happened so fast that my thoughts felt slow and sluggish by comparison. So I sat there and waited for someone to tell me what to do.

When my mum got home she ruffled my hair as she walked past and went inside. After a while she came out, the smell of chicken and vegetables coming out behind her, and she asked me to come in for tea. Then she asked where my sister was, so I told her. I watched her face scrunch up in terror like my sister’s had earlier. She grabbed me and shook me and things started to spin. She asked me why I hadn’t done something, why did I just sit there, was I stupid, and I didn’t know the answer to any of her questions. She started screaming at me and I didn’t know what to do.

Things happened fast after that, despite things not really moving at all. There were police cars in the garden and on the road, police officers in the house, police officers eating cake, police officers eating my cake. There were family members sitting in the living room consoling my mum, casting sad but blameful looks towards me on occasion, drinking tea, also eating my cake. They didn’t ask, however. There were reporters and television crews asking all sorts of questions, asking my mum things about my sister which she answered. Most of the answers were true, some she made up to add drama, I guess. Someone had given me a list of things to say beforehand about my sister and it felt odd because I knew about my sister. I knew her. I loved her. I didn’t need to rehearse how much I loved her. But I memorised the lines and they came out cold and distant, which strangely made everyone feel sorry for me even more. The person who wrote them didn’t even know my sister.

This circus went on for a couple weeks. It felt like I couldn’t go to the toilet without a reporter being at the door when I left the bathroom asking me how it went, was it a full bowel movement, anything else I’d like to add? I couldn’t walk around with only my pants on for fear of elderly relatives catching me and screaming in that theatrical way. So I stayed up in my room and remembered how close my sister and I were. I remembered the things we did together: playing out in the garden; walking to the end of the road where the woods appeared to have swallowed it and walking through them, hearing birds whistle, trees sway in the breeze, sunlight bounce as they swayed; walking into town and me not having enough money for sweets, for magazines, for comics, and her giving me her own money to spend. I would always say thank you and take it, never say don’t worry and not. As I sat in my own room, alone, it hit me what happened and I cried and clutched at my bedcovers. I wriggled until I’d wrapped them around me in a cocoon and I stayed like that for weeks.

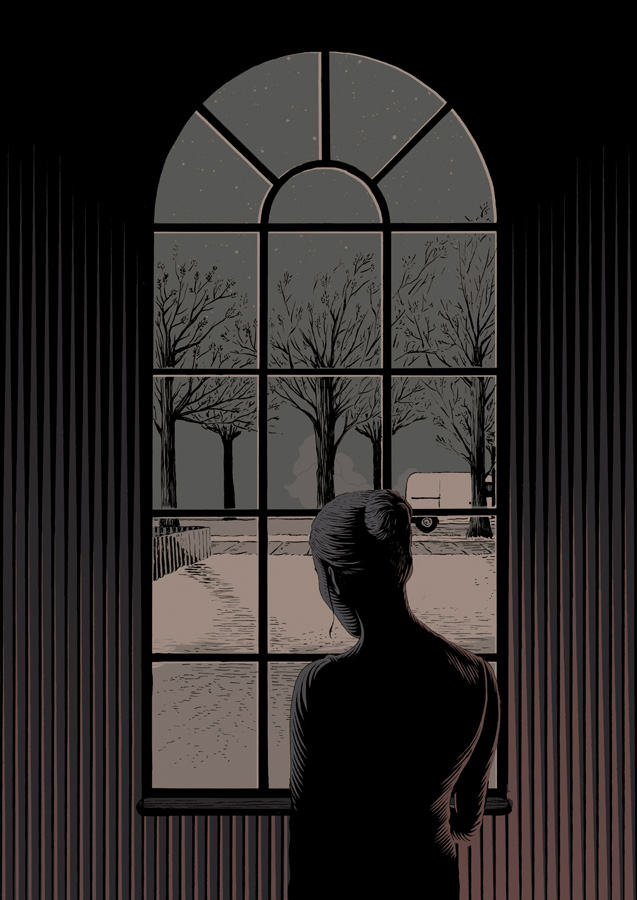

When I left my room a few weeks later the circus had died down. The flood had decreased to a trickle. Twenty police officers had turned into three or four and they weren’t eating my cake or talking to my mum so much anymore. The relatives decreased as well, most of them going back to whatever branch of the family tree they’d descended from. Reporters still came round but they didn’t bring cameras with them, just notepads, the news going from national to local. A few weeks later even that stopped, until the two of us were left alone with each other which was worse than the frenzy that preceded it. My mum couldn’t look at me and when she did, I could imagine those thoughts dancing through her mind, blaming me for my inaction. The two of us danced around each other, moving to different beats. I wanted to scream at her – what could I have done? I was only a boy! I just didn’t think! I wasn’t expecting what happened, I wasn’t prepared. She made me meals but she wouldn’t sit with me like she had when it was the three of us and, as far as I knew, she didn’t eat anymore. After a while I noticed the colour had dissolved from her face, as if she’d left it in another room somewhere and forgotten to take it with her. She was thinner and if eyes are the windows to the soul then you’d have to put your hands up to the pane to peer through hers. The light had disappeared from them, she was a dark and empty room. She was disappearing before my very eyes, over what felt like days but was actually months. School became important only if I remembered to go. People came round and asked my mum why I wasn’t going to school, and she’d sit and nod and pretend to take it all in, all the while staring out of the window into the garden, as if she expected my sister to be there.

And two years later, that was exactly what happened.

I was sitting out in the garden, reading. Mum was inside somewhere, lost. It had been my sister’s birthday a few weeks before and this one had been easier than the last one, the first birthday after her disappearance. I wondered if the people who had taken her had let her celebrate it. I wondered if they had at least extended her that courtesy. Sitting there I imagined the two of us, brother and sister, both forgotten in our own little corners of the world, discarded and alone; we’d been cared about for a little while but had become boring. Now my mum and I were left to carry on with our lives and pick up the pieces, but you can’t really; they’re so minute, the size of atoms, and they’re scattered as far as the eye can see and beyond.

And I looked up and there she was.

My sister.

It was her, I knew it. She had grown but I remembered her face. She had my mum’s face, only younger, but it looked like whatever my sister had gone through had made it catch up; she looked much older than she was.

I put the book down and stood up. We stared at each other, frozen, then I slowly walked over to her. She blinked at me, as if recognising me from somewhere but trying to pinpoint from when, from where. She had new clothes on and, for all intents and purposes, she was my sister; but there was something missing. I could tell that straight away. She reached for my hand like she was walking a tightrope and then fell into my arms. I held her up and we stayed there for a long time. I grasped her tight. We whispered to each other, tried to fill in the gaps of the last two years, clinging on to each other for dear life, just in case this meeting was temporary and she’d drift away. We peeled away from each other and I looked into her eyes. There were tears in them and she managed a smile. I put my arm around her and we walked into the house.

Mum was lying on the sofa, staring at the ceiling. It took a minute of us being in her eyeline before she made sense of what her eyes were telling her. She must’ve thought it was a mirage, more punishment from her thoughts, perhaps she was dreaming. But she wasn’t. This is real, I said. She fell into my sister’s arms and we all collapsed into each other on the floor. We stayed that way for not long enough.

The circus came back to town but the story had changed. It was one of relief, joy. I wasn’t handed anything to say and it all came naturally to me. The three of us sat together on the sofa while a reporter asked us questions. Cameras and lights honed in on us. We saw ourselves on the TV afterwards and we joked about how we looked. The police were questioned and they said how it was a miracle, a modern day miracle. They didn’t say how far they’d got with their own investigation. Eventually, much like before, the circus left town again. Neighbours came round and wished us all well – and we were well. We were complete again.

Things weren’t perfect, however. My sister didn’t just come back and reintegrate herself into her, and our, life seamlessly. There were hospital visits, visits to therapists, and my mum took to the habit of trying to pry information from my sister, but instead of using tweezers, decided on using sledgehammers. She’d become impatient, wanting to know the ins and the outs. I asked her to stop but my mum would turn on me, saying this was my fault, and it would descend into farce.

After a few months my sister was still distant. I don’t know what we expected. It was as if she weren’t there at all, as if she’d never returned, as if she’d left herself out in the garden that day and I was the one to blame. They’d borrowed her body but stolen her soul. She had come back broken, hollow and empty.

Mum couldn’t stop trying to tunnel her way into my sister’s mind. Even after months she couldn’t help herself. They’d have an argument as if it were my sister’s right to divulge that information, and I’d get involved and ask my mum to stop, and she’d blame me for letting it happen. Repeat. Over and over again.

For her part, my mum tried to bring us all together and act like the family we had once been. It was good of her to try, I guess it was the right thing to do, but it couldn’t happen. Not then. We were back together but we weren’t the unit that we had been before; we were barely holding on by our fingertips most of the time.

But as time went by, the closeness that my sister and I had before began to take shape once again. We resumed our trips into town, walking in the woods and, little by little, her personality started to reattach itself to her body, stitch by stitch, seam by seam. She never told us what happened to her and I didn’t pry. They were her secrets and it wasn’t up to me to go hunting. She was entitled to them and I wasn’t sure if I wanted to know anyway; I was scared of what those secrets might be.

But sometimes late at night, when my sister and mum had gone to bed, I’d sit out in the garden at night and remember that van, and think of how things could have been different, what I could have done, perhaps should’ve done. I’d stare out at that road, think of that day.

One night I was out there and found my sister had crept up behind me. She didn’t say anything, just sat down beside me and rested her head on my shoulder. We both stared out into the shadowy street, everyone else fast asleep. I knew my sister had come back altered, a surgery of the personality, but it wasn’t just her; something had left me when she was taken as well. The pair of us were missing parts and, staring out into the shadows with her head on my shoulder, I liked to think those parts of us were out there somewhere, sitting in another garden much like this, playing and laughing, and should a van come and a door open revealing an interior darker than shadow, we’d run inside and hide in my bed, the two of us cocooned under the covers, and wait for that van to leave us behind.

To ensure that you never miss a future issue of the print magazine, subscribe from just £24 for 4 issues.