WALL OF SKULLS

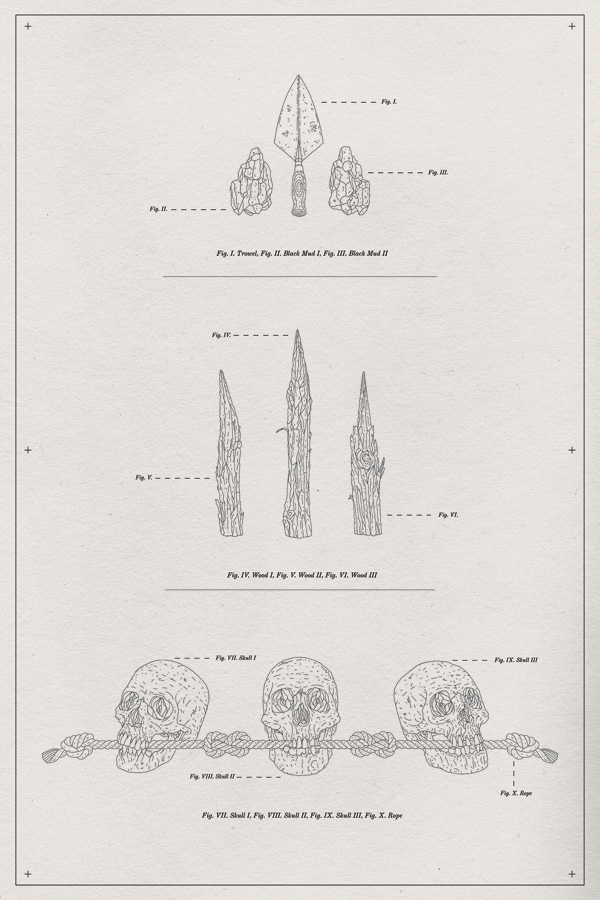

Barry Charman’s short story leads us to the infamous wall of skulls and the old woman who lives in its secretive shadow. Illustrated by Bradley Jay.

The old woman lived alone in a land where nothing could live. The soil was dead. What few plants there were, turned from the sun and withered through choice. Where weeds sprouted, they were black and despairing like the ground that bore them. Nothing else grew in the shadow of the wall of skulls.

The young man dropped his satchel and stood awhile, staring at it, awestruck and terrified. In the village, when they heard the wind roaring across the land, they often said the wall of skulls was screaming.

As a boy, he had huddled beneath his bed sheets and trembled at the thought of those moaning dead. He remembered the first time that he and some of the other boys had gone to see it, how it had leered through the early mist, and emerged like one of his nightmares.

The others had run. He had stood, and stared. They had walked all night to reach it, and when he finally saw it, he wanted to truly understand it.

He remembered that first time, as he stood and tried once more to understand. The wall of skulls had always been there, so long that no one could tell him how it was built or by whom. There were old tales, passed down and told and retold, but no one ever spoke with the surety of truth. No one really knew.

It screamed into the sky, towering hundreds of feet above him. Black clouds rolled over it from the land beyond, the unimaginable land beyond. Had they built it? Whoever — whatever — lived on the other side? Did anything live there? The young man had no answers. So he simply did what he always did, halted and allowed himself time to ponder.

The old woman never came into the village; she needed a walking stick now and couldn’t make the journey. Twice a week, someone brought her food, sometimes the young man, sometimes his sister, sometimes someone else. The old woman unnerved him a little; she had strange ways. Why had she chosen to live out here, in her rundown shack, alone in the shadow of the dead? And why had she no family, who could provide for her themselves?

He crossed the desolate land and made his way to her hut, which stood alone and apart, the only thing built here that was not made from bone. On an overcast day, the land was as black as the sky; sometimes the moon separated the two like a blind eye.

His feet kicked up patches of strange white sand that always itched his nose. There was an earthy smell of rot that often followed the rain. His father told him there had been a forest here once, he wondered if its dry roots had survived, and yearned towards the raindrops. Was it that echo of life that stirred and smelt like some other place still living?

He knocked on the old woman’s ragged door, and stepped back as she opened it. She was thin, but you couldn’t call her frail. There was flint in her eyes, and a sharpness to her words that could cut through any foolishness. She took the package of food from him, muttered her thanks and turned to close the door.

‘I wondered-‘

The words slipped past his lips, but as she turned, he couldn’t finish the question. Instead, he glanced up at the wall. How many hundred feet? How many dead compiled from what war? Such a war that no one had committed it to memory or history book.

She followed his look, then darted him a hostile glare. ‘What?’

He took a deep breath. ‘I wondered if you knew who lived on the other side?’

She slammed the door without a word.

The young man shook his head, and started walking from the hut, taking a stroll by the wall — something he rarely did. Such a hideous thing it was, made of so much death. Bone lashed to bone, bound by thick rope and black mud. So much time had been given to it. He wondered if men had even died making it. Had they been given to the wall as well? He shuddered. Wandering close, he noticed something that he had never seen before; there were crude pieces of wood sticking out of some of the skulls, protruding from their sightless eyes. He pondered this for a while, before he looked up, and realised with a start what they were: holds, for climbing.

Later, with the wall still on his mind, he made his excuses to his parents, and returned to it. He found an overhanging rock that he could lie on, and watch the hut from a ridge without being seen. He waited, but nothing happened.

The next night he watched, and then the next. On the third night, the wind picked up, and he saw the old woman emerge stiffly from her hut. She pulled her heavy coat around her and walked a little way to the wall. Then the wind found the skulls and they sung her a woeful song. She stood a while, listening. Eventually, she slumped and returned to her hut, lighting a small fire for herself in the dark.

The young man had seen nothing to unnerve him. He thought of how he was wasting his time, fearing that the shadow of the wall had infected him with whatever macabre thrall had infected her. However, on the fourth night, he saw the old woman leave the hut again and walk to the wall. He watched as she stood at its base, and prepared herself. Then, she dropped her stick and began to climb. She used the pieces of wood to get started, then higher up, started to use eye sockets for grips instead. Up she went, climbing row after row of skulls, until she became a small dot in the distance, and disappeared over the top of the wall.

The young man was shocked. He didn’t know what to do. So he did nothing — he just watched, and waited for her to return. Shortly before dawn, he made out her figure, bent and weak but able to lower herself, slowly but surely. Eventually she made it to the ground, and he went forward, meeting her before she could reach the hut.

‘What is on the other side?’ he begged, years of curiosity rushing from him. Perhaps it would have been wiser to tell someone else what he’d seen, to not tell the old woman at all, but he could not bear it. Never had he heard of anyone climbing the wall, and never had anyone suggested what might be on the other side.

The old woman was tired, but she studied him, then told him. ‘The other side is a wall of flowers, white and glowing. Beneath and beyond, not far, is another village, not unlike your own. There was a war once; it cut down the young and the old, and the young and the old that replaced them. And when it ended, each side built the wall. One made a symbol of the dead, and kept to the truth of dying; and the other covered the dead with glory and beauty.’ Her face twisted at this. ‘I have lost sons to other wars since this, and when I think of them, I think only of the pain of death. The pain is as real, as the glory was a dream.’

‘So I chose to live on this side of the wall, where death was respected. Where death was a shadow made to be cast over life.’

The young man listened intently. When she finished, he stared up at the great wall in shock. ‘Do they know?’ he asked, ‘that this side is a wall of skulls?’

She shook her head. ‘Few do. Mainly mothers. Mothers without young.’

She told him then how she took food to some of her relatives, who lived over the wall, in the bright shadow of their adored dead.

‘It is a good climb,’ she added. ‘Every moment evokes life and death, and the memory of both.’ With this, she turned from him, and went wearily to her hut.

The young man stood there for a little while, then turned and looked to the wall. Ever since he was a boy, the great wall had appalled and terrified him. He’d imagined all those people dying, so long ago, and then their heads being assembled on the wall. Dragged and hauled into place. There forever, side by side.

Now, he imagined the white wall beyond; a high, endless, curtain of bright flowers swaying elegantly in the breeze, and everything beneath covered up, decorated, forgotten. Appalled anew, he turned away, and began the long walk back to his village.

To ensure that you never miss a future issue of the print magazine, subscribe from just £24 for 4 issues.