FATHOMING

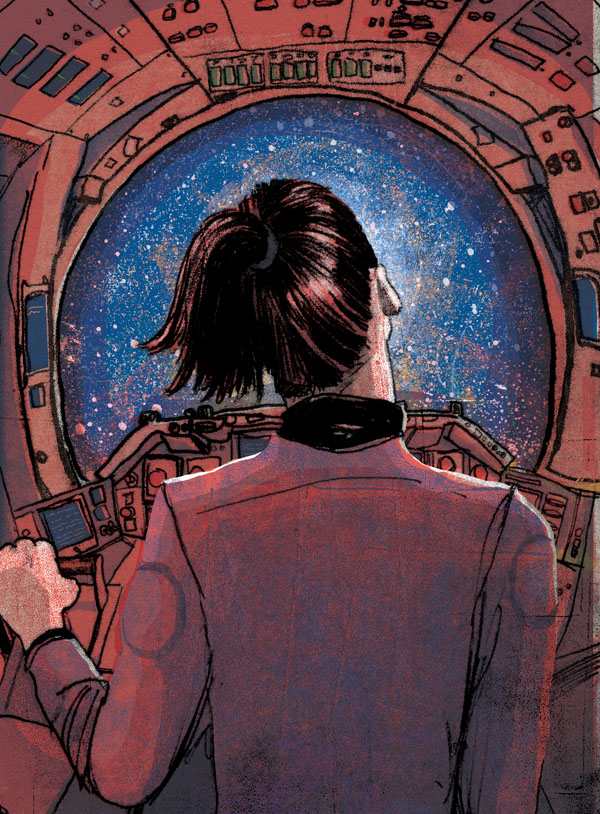

A father watches his ocean-loving daughter embark on a perilous deep sea expedition in Dan Coxon’s fretful short story. Illustration by Luke Waller.

In 2031, with the discovery of the Fais Crevasse, mankind turned its eyes back to the sea. Fifty-seven miles long, the Crevasse ran along the bottom of the Mariana Trench. Nobody knew quite how deep it went, but drones had registered depths of over 40,000 feet. In its midnight waters, the public imagination was held captive.

It took two years, four months and five days to build the Aronnax. In total, it was estimated that over thirty-two million Euros were spent, making it the most expensive international deep-sea project ever. The end result was a seven foot by ten foot capsule, designed to withstand pressures of over eight tons per square inch. Onboard computing systems would control the descent and ascent, monitoring and — if necessary — treating its single occupant, while external cameras, lights and robotic arms could examine and interact with the lifeforms it discovered. Piloted drones had been down to similar depths, but no living person had previously drawn breath so far beneath the surface of the ocean.

On June 15th 2046, my daughter Bethany would be the first.

Beth had always loved the sea, ever since she was young. While Alice was still alive we’d spend a week each year down in Devon, exploring the countryside and the unspoilt coastline — before the seas rose and swallowed half the county. She tolerated our trips to cider farms and fudgy gift shops, but all she wanted to do was pick up her net and spend her day trawling rock pools. We’d gather tiny crabs as they scuttered over the sand, darting fish the size of matchsticks, gelatinous anemones, coiled shrimp. Before we drove back to our rental cottage she’d return them to their habitats, taking care to place each one back where it belonged. With Beth, it was always about the discovery.

A month before the Aronnax was dropped into the ocean, Beth came round for dinner. I cooked chilli dogs on the grill and made homemade coleslaw, peach cobbler and custard; her childhood favourites. She told me as we ate that the other scientists were focused on drawing lessons from the tidal data she’d bring back, trying to understand the ocean’s currents. Parts of Kent were considered under threat now and the East Coast of America had lost three cities in five years. If there was any hope of holding back the rising tides, maybe it lay in understanding the deep. But I could tell from the tone of her voice that she didn’t include herself among them. She had always been about the wildlife, the joy of discovering living things in the least likely of places. She didn’t have to say it out loud. I knew that she wanted to find out what might live in such an inhospitable place. It was in her nature.

I couldn’t go with her when the expedition pushed out to sea. With the amount of equipment they had to carry, spaces on board were limited. They welcomed me into their laboratory instead, and even paid for a hotel room. My daughter was the hero of the hour, which made me royalty by association. As they neared the release point — directly above what they thought was the centre of the crack — we gathered in front of a bank of screens. I recalled the Apollo launches from my youth, before mankind turned its gaze away from the stars.

Beth stayed in video contact while they lowered her into the waves. Emotion swelled in me as my little girl’s face filled the screens, pride and fear struggling for control. There was no turning back now. Maybe there never had been. The first part of the descent was simple enough, a voyage undertaken so many times that it barely registered as travelling at all. Beth had checks to make, readings to monitor, but the atmosphere was light-hearted. The music playing in the pod could be heard over our speakers, crackling tinnily across the miles. When Rolling in the Deep — one of her childhood favourites — came on the playlist, there was a knowing chuckle among the technicians. This was what they did. Just another day at the office.

It was when she hit 36,000 feet that the expedition began in earnest. You could see it in the focused expressions, hear it in the terse radio conversations. They had done their best to boost the signal from the pod, leaving a trail of beacons behind in its descent to relay the pictures back, but even I saw that it grew grainier as she dropped. I could still see the joy in her smile as she encountered one of the trench dwellers, sending back blurred pictures of what looked like a string of pulsating fairy lights. To Beth, this was just one big rock pool.

They lost video at 39,000 feet, but radio communication remained open. As she passed the lip of the Crevasse she let out a triumphant whoop, the miles between us translating it into a fuzzy burst of static. Three minutes later, the radio died too.

One of the technicians offered to get me a coffee. They’d expected this and Beth had warned me: where she was going, there wouldn’t be phones. A tiny red light on one of the displays still monitored the pod’s descent, deeper than humankind had ever gone before. Another programme tracked her heartbeat, her blood pressure. My little girl reduced to a scrawl of wriggling lines.

And then those stopped too. I could feel the atmosphere in the room change, a drop in pressure caused by fifty people all sucking in their breath. We waited for the pod to come back online, but there was nothing. The murmurs gradually gave way to silence. We stood and watched, helpless, willing her back into existence.

After three hours, someone suggested that I return to my hotel room. The waiting was turning frantic now, as everyone looked for someone or something to blame. They’d call me, they said, when there was news. Who knew what might be going on down there, what she might have encountered. We shouldn’t give up hope. The pod was designed to be habitable for up to two days. They could still bring her back.

In my hotel room, among the characterless greys and beiges, I felt numb. Someone had warned me to stay away from the media coverage, but I couldn’t help myself. The lab was closed to visitors, and the TV panel was my only lifeline. Beth was the talking point of the moment, the valiant hero who had risked everything for the betterment of mankind. They didn’t start to talk about her in the past tense until well into the second day. On the third morning, I started receiving condolences. After a week, they stopped paying for my room. I packed my bags and returned home, alone.

It was almost a month later that it happened. I might have missed it if the TV hadn’t still been murmuring in the corner of the kitchen. It had become a habit, that murmur. I couldn’t make it through the day unless there was the hum of voices in the background. It was the only lifeline I had left.

The daytime presenter was interviewing a rising young actor when they interrupted. A news story was developing fast, they said. They’d tell us more when they could, but it appeared that there had been an occurrence at the Aronnax laboratory. Most reporters had long since departed, but someone must have left a skeleton crew behind. There was a shaky handheld shot of the room we’d stood in, the bank of screens that still appeared sometimes in my sleep. A few technicians were huddled, some holding hands to their mouths, others staring slack-jawed at something off camera. The image panned across and there it was. The pod, the Aronnax, returned to us.

Details gradually trickled through, hidden in the recaps of Beth’s bold drop into the unknown. I tried to get through to the lab but it rang out. After a couple of hours, all I got was the dialling tone. From what I could gather, flicking from channel to channel, there had been no warning. One minute the room had been empty, the next the pod had been there. Dry, unmarked, intact. There was no explanation, no language to even describe what had happened. The experts they called in to explain the phenomenon were as clueless as the rest of us. The word ‘miracle’ was uttered more than once.

It was early the next morning, as I sat on the bed staring at the flashing lights on the screen, that a representative from the lab finally called. It took me a few seconds to realise what the ringing sound was. Yes, she said, the TV reports were true. In what she called an ‘unprecedented occurrence’, the Aronnax had reappeared in the lab, without warning or explanation. Yes, they had opened it. My daughter was inside. She was alive, somehow. No, they had no official explanation of what had taken place. It was, as far as they could tell, completely impossible. Modern science had nothing to offer.

‘Can my daughter not tell you?’ I asked. ‘Can Bethany not explain where she’s been all this time?’

There was silence for a moment.

‘Your daughter is not entirely unscathed,’ she told me. ‘She seems to have lost the ability to speak, or write. She hasn’t tried to communicate with us at all, she just wants to stare into space. We don’t know quite what to make of it.’

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t care. Of course I did. What parent wouldn’t. But the fact that my girl was still breathing trumped everything. The sea had taken her, but someone — something — had given her back to me. Let the scientists worry about the rest.

I finally saw her nineteen days later, in a secure facility in Greenwich. They were monitoring her, with little success. All the data said she was healthy. But she looked thin, and hollow, the victim of some unknown trauma. She was eating, they said, but only the bare minimum. Just enough to stay alive. When I stepped into the room she looked up, briefly. Then she went back to contemplating the wall. I held her hand for an hour, just to feel her, to convince myself that this was better than nothing.

Tomorrow she comes home. The scientists say they’ve exhausted every avenue. They’ve monitored and tested her until, finally, they’ve had to admit that they’re floundering in the dark. When she gets here, I’m going to load up the car and drive us out to the coast. I have a beach in mind, in North Devon, one of her favourites when she was a child. I’ve already packed two pairs of wellies, a net and a bucket. We’ll see what we can find.

To ensure that you never miss a future issue of the print magazine, subscribe from just £24 for 4 issues.