THE ARRIVAL OF MISSIVES

Set in the aftermath of the Great War, an exclusive excerpt from Aliya Whiteley’s brand new genre-defying story of fate, free will and the choices we make in life.

I cannot sleep.

Today I overheard Mrs Barbery in the street gossiping with the other mothers. She said, ‘He isn’t a real man, of course, not after that injury.’ I walked past and pretended not to have heard. He limps, a little, but it does not constrain his activities. Sometimes I wonder what is under his shirt and waistcoat. I imagine something other than flesh to be found there: fine swan feathers, or a clean white space. No, Mr Tiller is not what passes for a real man in these parts, and all the better for that.

My feelings for him have infused every aspect of my existence. My heart leaks love; it seeps out and gaily colours the schoolyard, the village green, the fields I walk and the books I read. My father comes back from his work at times and finds me in the armchair by the front parlour window, curled up in thoughts I could never dream to share with him. It has become a ritual with him saying, with a smile, that I have a talent for wool-gathering and that he’ll sell me to the shepherds.

My mother sometimes brings me tea, creeping into the parlour as if she does not quite belong there. She bears a curious expression in these moments, perhaps best described as a mixture of pride and worry. It troubles me. I think she knows my mind, even though we have never spoken of it. She was once an uneducated version of me, of course – the raw clay from which I am formed. But then she returns to the kitchen, and there she is a different woman, bustling to and fro, laying out plates for the workers at the long oak table. The workers are the remains, and the reminder, of the war, but they work hard, as does everyone on the farm, including the animals. Apart from me. I am marked for something else.

This is a different age, a new era, and my feelings are all the finer and brighter for my luck in having the time to explore them. The upward path of humanity, out of the terrible trenches, will come from the cultivation of the mind. And women will have an important role in this, as teachers, as mentors, to the exceptional men who will grow from the smallest boys, with our guidance.

Once I asked my father if, once all the young men were dead, they would send women to fight at the front, and he said I had the mother of all imaginations. Well, that is what is needed now. After such a war people must think new thoughts, give birth to lofty emotions, and love is surely the best place to begin. I am in love. I am in love: Shirley Fearn, landowner’s daughter, is filled to the brim with love for Mr Tiller.

Look how love coats me in a shiny slick that no grim thought can penetrate. It lights the dark, and distinguishes my being. I am set alight by it. Love no longer belongs only to Byron and his like – to the real men, as Mrs Barbery would have it; it is now the province of schoolgirls and cripples. It is, for the first time, universal.

Besides, I am not so very young, and could have left school two years ago if my father wished it. I am about to turn 17 years of age, and Mr Tiller only limps a little.

Outside my window, the owls screech and the leaves of the trees murmur and hush. I can picture the branches swaying in the breeze. The fields have been sown and the crops are growing, slowly pushing from their hidden roots. The worms and moles are there, burrowing blind, busy busy busy in the earth. Such thoughts of dampness in the dark quiet my mind, and lead me down to my sleep.

The land is green and sweet. The walk to school – a few miles from the farm to the outskirts of the village – is easy in late spring, and these are my father’s fields upon which I tread. I grew up with them, and I know their rotations and their long, ploughed lines. In summer they can be headstrong, and fight my progress along their hedges with thistles, nettles and squat, tangling weeds. When winter comes they turn into a playful mess of mud, determined to swallow my boots. In such weather, by the time I reach the school I feel as if half the field has come with me; on one occasion Mr Tiller looked at me and said, ‘Out!’ upon my arrival, before I made a state of the flagstone floor. The others laughed when I sat outside and tried to prise the knots from my laces with frozen fingers, blushing at my own incompetence. But Mr Tiller came out to me then. He knelt by me, and helped me to cast off my boots and forget his harshness.

Undoubtedly I prefer these spring days. It’s easier to dream when the mud does not drag me down.

Here is my plan: Mr Tiller and I will marry, and I will become a schoolmistress to raise the finest generation yet known to England.

Well, to be precise, that is the culmination of the plan. First I must go to Taunton and earn my teaching certificate, and I will cram all life into those years so that I can settle with ease when I am married and I return to the village. I would hate to have regrets. Bitterness in a teacher can spoil a pupil, I think.

The last field ends in a stile that intersects with the new road, and I hop down upon it and follow it onwards. It’s easier walking here, but I dislike the sound my boots make on the stone. The village is over the curve of the next hill. I have friends there, other girls my age, but I have yet to find a close companion of the heart. I want to find others who dream, like me. Or perhaps I would rather that this weakening need for company would pass. I do not think mingling with lesser minds would be good for my intentions.

I crest the hill, and there is the village. It seems quiet from here but it will already be alive with tradesfolk, meeting and murmuring about their daily business. I shake out my skirts, square my shoulders, and walk down to the yard, looking neither left nor right.

The younger children are skipping, singing songs. The clock in the steeple ticks down to nine o’clock. I go inside, taking care to wipe my boots clean on the mat, and find the classroom empty, the blackboard wiped, the slates not yet set out upon the desks. Mr Tiller is late. This is not unheard of, and it does not worry me. I go into the small store room, where the rows of shelves hold chalk, beaten books, rulers and other delights of the teaching trade. I take out the slates and start to set them out on the desks, looking at the messages children from then and now have carved into the wood. They must all leave their mark somehow upon this place, even if only their letters remain.

The clock bell strikes, and the children come in. There are 12 of us, of varying ages; I am the eldest. Our desks have been allocated according to age and ability. I sit at the back, on the left, next to the spinning globe of the world – a position of responsibility, since the younger children would spend all day with their grubby little hands upon it. Behind me is a shelf that bears the bound works of great minds that have gone before. ‘If you are seeking inspiration,’ Mr Tiller once told me, ‘take down a book from that shelf, Miss Fearn. You have a keen mind. Let the books take your intellect to far-off places, and who knows what you may find?’

The children are noisy today, even the older ones. The blacksmith’s boy, Daniel, enters with a yell, and sees my frown.

‘I tripped on the step,’ he says.

I take a breath and move to the front of the classroom, putting the blackboard to my back and pulling myself up straight. They pay no attention, so I clap my hands together. They find their desks and fall quiet.

I am about to speak. I am sure some words of wisdom are about to flow from me, to prove that my dream of a scholarly vocation is a worthy one. Wait – nothing is coming—

Wait—

‘Mr Tiller says go home!’ shouts Jeremiah Crowe, who is nothing but trouble, and the children scream. The smallest ones even start to get out of their seats.

‘No, Mr Tiller does not,’ says that familiar voice, the one that bolsters my faith, and he limps into the room at speed, to stand beside me. ‘You are too impertinent, Crowe, as ever, and you’ll stay late to clean the slates tonight. Right. Let us settle ourselves and prepare for learning about one brave adventurer, Marco Polo, and the wonders of the Orient.’

What should I do? Should I sneak back to my place as if I never tried to take his? I wait for a word from him, but nothing comes; he turns to the blackboard and picks up chalk from the wooden lip of the frame. He wears no coat today, and I watch the muscles of his back bunch together under his shirt as he writes, marking out the M, the A, the R.

‘Sir,’ calls the irrepressible Crowe. ‘You haven’t taken register, sir.’

‘I thought Miss Fearn would have completed that task. Well, no matter, she can rectify the oversight now.’

I am raised high, and all the little faces turn up to me as I move to the teacher’s desk as in one of my dreams. I call out the names and mark the list. We are all here. From despair to triumph in a moment – how unpredictable my life is! I finish the task and look up to find Mr Tiller smiling at me, an expression not just of pride in a student, but perhaps in a future companion? I am moved beyond delight. It is as if he too has pictured our future, and found it pleasing.

I sit in my room, listening to the men eat their supper at the kitchen table below, and compose my letter to the newly founded Municipal Teacher Training College for Women.

I write of how I am inspired to teach by my own instructor, and how I am already of use to him in the classroom. I write of my knowledge of Lamb’s Shakespeare, of Keats, of my understanding of the parts of Chaucer that are considered suitable reading, and of how I excel at the multiplication of large numbers. I am proud of how the passion within me becomes visible on the page.

I keep writing, and find myself explaining thoughts that solidify into purpose. I explain how cultural beauty only enhances our connection to the natural world, and is only a refinement of our urges to walk among flowers, touch tree trunks, squint up at fierce sunshine: this is all true learning, too. Those from farming stock can possess as fine a brain as an Oxford scholar, if he is shown the way to use it. My handwriting falters in the excitement of elucidating such ideals, but still, it is an impressive letter in its fullness. I have stated my case.

I will post it tomorrow.

I light my candle as evening falls. The workers are loud, and merry. I will read for a while, as I listen to the hum of their conversation through my floorboards.

I post the letter and receive only a mild interrogation from Mrs Crowe at the counter.

‘That’s tuppence. Does your father know you’re writing to colleges?’ she says. She wears a white ruffled blouse with an air of superiority, but she looks swollen and pained in the way that I have noticed happens to many women in the village once they have had many babies. The two youngest Crowes, a toddler and a very little one with jam on its chin (at least I hope it is jam, and she is not raising carnivorous primitives who work at raw meat to be sated! There goes my imagination again), sit in the post office window and wave at the people who pass. The rest of the Crowes will have already departed for school, no doubt, in the cleanest clothes they could muster. I will be late myself if this conversation continues for much longer.

‘At this stage I am only enquiring, Mrs Crowe,’ I say. ‘Exploring all possibilities.’

‘Are you now?’ she says as she puts the letter under the counter. ‘That schoolmaster will have a lot to answer for if he’s putting grand thoughts in your head.’

‘Mr Tiller has not encouraged me,’ I say, and that is the truth. I know honesty shines from my face. Mrs Crowe looks confused, then smoothes her ruffles. The toddler starts to bang on the window, and as she moves to retrieve him I take the opportunity to flee.

The day passes in the ongoing company of Marco Polo. What an adventurer. How wonderful it must have been to be Polo’s teacher: to encourage his ingenuity, his desire to see all, learn all, and hear about it upon his return.

‘Pay attention, class,’ says Mr Tiller, ‘even you, Miss Fearn. I see you at the back there, daydreaming about your own visit to China one day.’

I catch his eye and say, ‘No, Mr Tiller, I was not dreaming of that at all.’ Let him make of it what he will. I like the confusion that springs into his eyes, and the way he tilts his head.

The hours pass slowly. I watch him for the rest of the day, feeling quite certain that I’m doing the right thing, and that he needs to know of my plans. Finally, the school day is done. When the children are gone, I loiter, and Mr Tiller looks to me with raised eyebrows. His voice is that of a schoolmaster. ‘Go along, then, Shirley.’

This is not what I want. But I find I must be given a window of opportunity to speak as a woman, not as a child. He is using his superior tone against me. I look at his hands wrapped around the worn textbook he holds. I see him tremble, and then I understand. He is trying to keep me away.

‘Yes, sir,’ I say, and I leave the schoolroom. I emerge into the late afternoon sunshine alone, with the children already scattered for home, or maybe to the bakery to see if Mr Clemens will part with any of his stale buns for no more than a smile.

I will soon be expected back home, but I find I cannot turn in that direction, because I have seen Mr Tiller’s trembling fingers and I know I am the cause. I cannot think of anything but those fingers. The village is unaware how much has changed in the last few moments, and how much I am changing within it. I feel strong, powerful, ripe with possibility. I feel it. I walk out of the yard and turn away from the road home, walking with what I hope is the air of a girl on an errand with every right to be travelling in an unexpected direction.

I was right. There are a handful of girls and boys in the bakery. I spy them through the window, but they are too preoccupied with badgering Mr Clemens’ daughter, Phyllis, to see me. Along the row of shops, I cast glances through each window in turn and only see myself, reflected. I am unremarkable, surely, from the outside. Why would anybody look twice, unless they knew me well and could see the change upon me through my white skin, lurking within?

My luck runs out at the church. The wall that runs along the graveyard is high, but not high enough; I catch sight of Daniel Redmore’s golden hair, and before I can duck he has turned his head. His eyes are the brightest blue I have ever seen them, and his face is red and swollen. He is crying.

I walk on before he can decide what to say to me. I know what he’s doing, anyway. He stands at his mother’s grave. She was kind and good, and lost to the influenza not so very long ago, so I suppose a boy can cry for her still. There’s no shame in it. Although it is different for women, I know that my mother still weeps for the children she bore after me. They were born not breathing, yet were perfectly made to the point of having hair and fingernails that she trimmed herself, and now she keeps those trimmings in a mother-of-pearl box upon the mantelpiece. They do not lie in the churchyard, as they could not be baptised, so my father buried them in the kitchen garden from boxes he made himself.

I don’t weep for these lost siblings. I never knew them, even though they all have names: Thomas, Arnold, Henry, Frederick. I feel no particular sadness for them beyond the pain they have caused my mother. But I can appreciate how great a loss Daniel feels, greater still than my mother’s; after all, he knew the intricacies of his own mother’s spirit, and had grown within its shelter. She was a fully grown tree, her boughs curved around him. She was not simply the first sprouting of an acorn.

I hurry on, and decide that I will not tell a soul that I caught him crying. In return I have to hope that he will not mention my passing presence outside the church. This could be our unspoken pact, if he has the sense to understand it.

Past the church there is the row of cottages where the families that no longer have fathers live by the grace of the parish, squeezed into small rooms with Mrs Colson and Mrs Wells taking in washing when they can get it, and then the road curves around, the hedges spring up high, and there is a loosely pebbled lane leading off, downwards, in the direction of the river.

The trees grow over this lane, forming a darkened tunnel, and the birdsong is loud at this hour. My boots skip over the pebbles with purpose as I approach my love’s cottage. His house is a little way from the village, where the old sisters Wayly once lived. They died within a day of each other, from the influenza. At the funeral the Reverend Mountcastle said he thought they never wanted to be parted from each other, but I thought of how they never served a cup of tea without a saucer, or a slice of cake without a fork, and simply considered themselves to be a matching pair for the sake of neatness.

The garden is not so neat now. Mr Tiller is not a gardener; well, why would a man grow seedlings when he can nurture souls? And I like this wild tangle that protects his door. The roses, no longer trained, do not follow the latticework, but grow out at stubborn angles from the wall to escape the shadow of the house. And the vegetable patches, one on either side of the path, have the rocky clumps, weeds and stones of a wilderness upon them. Where do these stones come from? My father’s fields fill up with them throughout the year, and they must be removed come the spring. It’s as if they work their way up through the earth at night.

The grasses have grown so thick around the walls of the house that I have to push them aside, but at least there are no nettles. I am able to work my way around the corner of the house and then crouch down without worrying about stings and scratches. I find a hiding place; I am ensconced amongst green leaves with the delicate fronds tickling my ears and teasing my hair. I will have to comb my hair out carefully later. Later, when I return to my room and face my father’s wrath for my lateness, I will be a changed woman.

With time to waste, I must consider my plan. Do I have one? No, I am being impetuous, and this is not how I pictured it. But he would not give me the opportunity earlier and so I must make my own chance to explain my feelings to him. He cannot escape from this place; this is his last resort. Besides, I like that word – impetuous. What is the point of being young if one cannot attach the adjective ‘impetuous’ to it?

There are too many questions in my mind and I cannot still my thoughts. They germinate, sprout and form beanstalks that raise up into the sky. I am picturing a wedding in summer with a cornflower and sweet William posy to hold when I hear the door open, and then close.

How could I have missed his footsteps on the path? I thought I would have time to steel myself at his approach, but he is close now, so close, and already in his cottage.

I cannot breathe, but I must. I cannot. I listen for him; I am a rabbit, with tender ears quivering. Has he headed straight for his kitchen? I picture what my father does when returning from work: leaving on his boots, to my mother’s disapproval, and looking in the pantry for something to eat before seating himself in a chair before the kitchen fire. I can envisage any man might act in such a fashion, although maybe Mr Tiller brings down a book from a shelf and actually does unlace his boots and place them tidily by the door, as a gentleman should.

I hear a scrape close by – the sound of a chair along the kitchen floor, perhaps? He is sitting so close to me. If I stood up now, he would see me. I would be as a vision to him, and a wild one at that, with ferns in my hair and a flush to my cheeks that is far from ethereal. I can feel my face burning with heat, although I am not ashamed. It is the excitement of the moment, but how could I persuade him of that? That I feel no embarrassment in my love? He would think me young and stupid, and possibly the instigator of a ridiculous prank, which would be unbearable.

No, I should work my way back to his front door so that I can straighten my shoulders, throw out my chest, and bang upon it with purpose.

But I cannot do that, not when I do not know what my welcome would be. I must see his face first, just a glimpse of it; I must see the man, not the teacher. Then I will be able to address the man as an equal, no matter if he tries to play the teacher with me.

I can imagine him eating methodically, possibly upon a dried apple or a wedge of cheese, with his mind on his book of Wordsworth’s verse, or on the lesson for tomorrow. He will be lost in thought. He will not see if I lift my head, just a little, until I can spy him through the window. He will not see.

I shift to my knees amidst the ferns, relieving the ache in my thighs, and then inch my way upwards so my view through the window changes: the low black beams of the kitchen from which hang dusty copper pans; the top row of serving plates upon the tall dresser; an ink drawing of a robin, the eye a black watchful bead that spies me, hanging in a gilt frame from the wall. Then a crown of brown hair. I raise myself just a little more, balancing on the balls of my feet, and I see his noble face, worthy of a bust from antiquity with the severe slope to the nose but a gentle draw to the eyebrows that softens all expressions. His countenance is cast downwards, deep in private reflection. He does not eat. He sits in a pool of yellow light from the lamp beside him at the table, and he slowly unbuttons his waistcoat. Still his fingers tremble.

I am imprisoned by my love for him. I cannot look away. He is unguarded; he thinks he is alone, but I am here. I am here! I belong to him, and I cannot be freed from the glamour his slow unbuttoning casts upon me.

He opens up his waistcoat and then commences upon the studs of his shirt sleeves. Then he reaches behind his slim, long neck and removes his collar. All the studs are placed upon the table. He slumps, as if these actions have allowed relaxation to come to him. Yes, this is the man. This is whom I wish to marry.

I should move to the door and knock, say my piece before the perfect moment is lost, but then I see his chin raise up once more, and he is about the business of his remaining buttons.

I have seen my father in his vest often enough, but it is not a vest that Mr Tiller begins to expose. It is skin.

No, it is not skin. It is the puckered edge of a thick scar, white and ridged at the hollow of his throat, leading down, and I remember what Mrs Barbery said – that he was not a real man. I am afraid of what I am about to see.

He unbuttons all the way down to the line of his trousers, pulls open the leaves of his shirt front, and then I see the scar is not a scar. It is a pattern revealed, which decorates the entire of his chest and stomach, and lower; I cannot comprehend so many lines and angles, made in his flesh. Except in the centre of the pattern, where there is no flesh at all. There is rock.

How can it be rock? It is solid, and juts forth from the bottom of his ribcage, making a mountain range in miniature, sunk into the body in places and erupting forth in others. There are seams of a bright material within it that catch the lamplight, and glitter, delicate and silvery as spider thread.

Mr Tiller places his hands upon the rock and throws back his head, his eyes closed, his mouth open. He forms words that I cannot hear; perhaps he does not speak them aloud. I am struck by the thought that he is communing with it.

He opens his eyes.

He sees me.

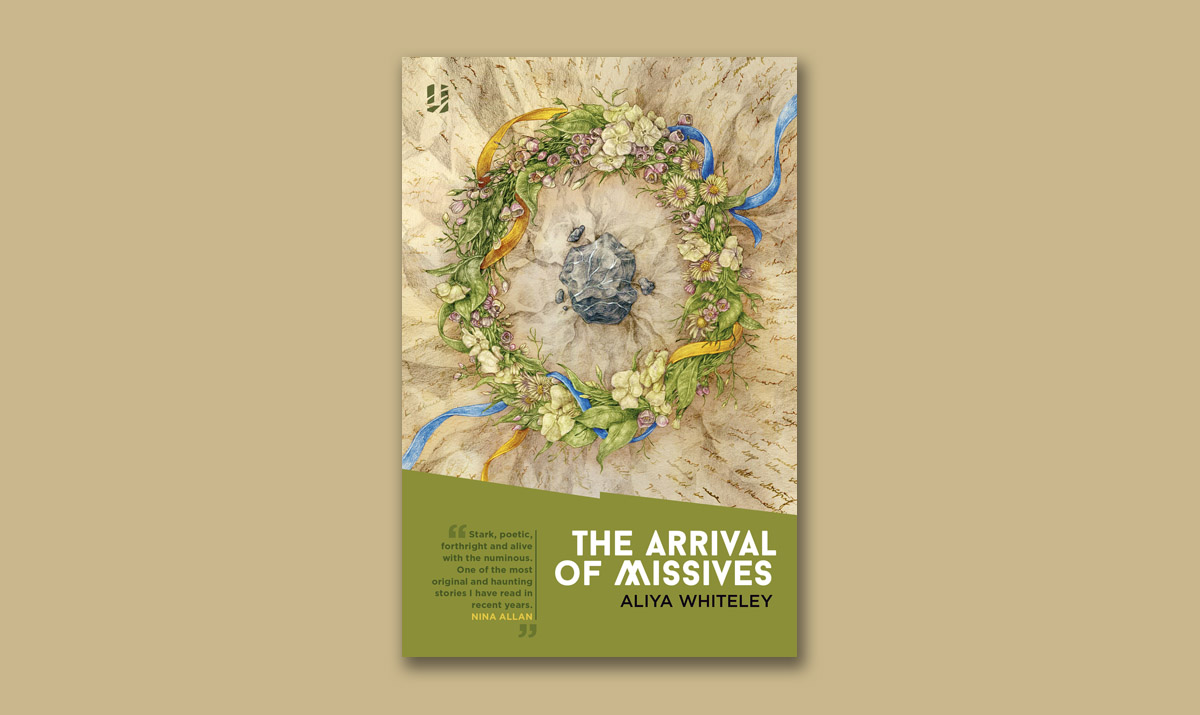

This is an extract from ‘The Arrival of Missives’, the latest story from Aliya Whiteley, published by Unsung Stories. Pick up a copy of the book at the Unsung Stories website.

To ensure that you never miss a future issue of the print magazine, subscribe from just £24 for 4 issues.