BUCKET LIST

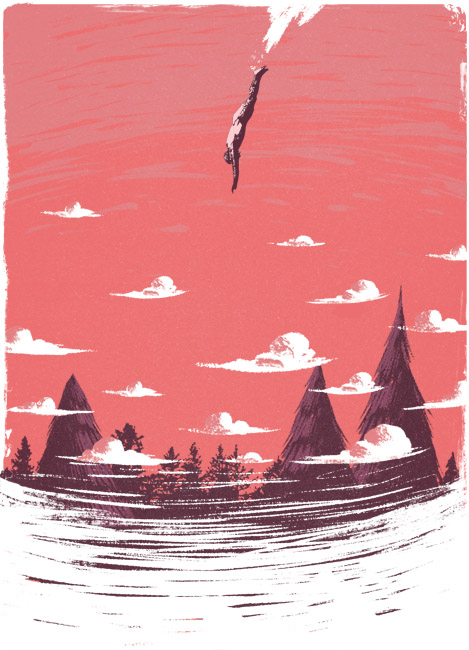

A tranquil hot air balloon ride takes a tumultuous turn in this riveting short story by Pete King. Illustration by Marie Bergeron.

The hot air balloon ride was a thirtieth birthday present from my wife, and a surprise. I was given a window of dates in June and told it would be a short notice call one afternoon from a local guy. It turns out the local guy was once a bit of a name and well known in ballooning circles. He brought his grandson along and our three other passengers included a man of about my own age, another in his sixties and a young woman who had to be helped into the basket by her parents on account of her disability — which I later discovered to be cerebral palsy.

The teatime air was blue, warm and virtually windless. It had been a near-perfect forecast, with the only doubt being the potential for thunderstorms. These would be confined to the west of the Pennines apparently, if at all.

Looking back, the irony of the balloon ride was that, for the early part, my principal emotion was one of vague boredom and I seemed to be the only one of the paying party that didn’t have this as a life’s ambition. Martin, the guy of my own age (but hopefully the only similarity) was like an incarnation of Google Earth, analysing and calibrating himself as we climbed and drifted. He didn’t dominate the conversation exactly, more enlightened us with a continuous commentary of the landscape.

‘So if that’s Bishop, then we’ve got Shildon just behind us and Crook over there. The Wear goes through them trees, that’s why it seems to disappear for a while.’

Nobody had asked him about the disappearing Wear; he was good at answering his own questions. I felt a little sorry for Sarah. With her condition she needed to hold the edge of the basket most of the time, which Martin mistook for keenness and so engaged her the most. The other man, David, who described himself only as retired, kept his own company in a quiet corner.

I chatted mostly with Rodney the balloonist or played sticking out tongues with his young grandson as he peered out from under his granddad’s legs. But to say it was totally dull would be disingenuous as the view was excellent and it was interesting to plot the landscape against familiar landmarks and settlements. Having not thought much about it beforehand, one of the things that surprised me most was the complete lack of breeze or rather, because we were floating with it, the lack of sensation of breeze around us. Our quiet voices echoed around us as if we were in a concert hall, giving it a strange god-like acoustic quality.

‘Where do we come down?’ I asked Rodney. It hadn’t specified the landing point in the literature. My wife was hoping to bring the twins and get a photo as Daddy descended.

‘I’m not sure.’ Rodney smiled as he gave the balloon another burst of flame. ‘Sorry lad, just having you on. I used to get in trouble with the company because they would tell the customer one thing but the balloon and the weather might think differently. See, this evening, when we took off I’d have said it would be a nice simple southwesterly that would float us somewhere near Sedgefield, but up here it’s decided to pull us west. If you need to let someone know, I’d say we might get as far as Hamsterley.’

And on we drifted.

Of course, the serenity and the vague boredom couldn’t last. I wouldn’t be telling it otherwise. The clouds that were meant to restrict themselves to the far side of the Pennines began to appear westwards. I saw them from a distance and so did the very quiet, retired, David. He turned and raised an eyebrow when he saw me staring. Martin kept up his chatter obliviously and Sarah politely held her attention his way. Rodney the balloonist said nothing but his actions began to betray his thoughts, and his nervousness. He began to lose us height.

‘Not going all the way to Hamsterley then?’

‘Err, no. I don’t want to use up unnecessary gas just to get there.’

‘Nothing to do with those clouds then?’

He glanced at the others. Only David was listening. Rodney put his fingers to his lips.

I can only compare the next moment to when a plane is waiting to take off at the end of the runway. All potential energy and instability. Our basket shook, even before the cloud engulfment and Rodney was suddenly pulling safety harnesses out of a rucksack and handing them out.

‘Clip on,’ he said assertively, and with precision timing. A few moments later, we were suddenly launched upwards.

We felt the wind then. It plastered our hair downwards and we climbed inside the vortex. Where previously we had been surrounded in deep blue, we were suddenly launching up through billowing grey. A smokestack of maelstrom and volatility. And it wasn’t short-lived or pleasant. The basket began to tip, first one way and then the other. If it wasn’t for the harnesses then we wouldn’t have all stayed in. It pulled us upwards and sideways. Still we climbed and rocked, still there was no visibility. And then, despite the vertical wind, I became aware of the thinness of the air. How high were we? Rodney’s grandson was crying. Sarah shrieked once and then shut her eyes, her knuckles white on the rim of the basket. The men said nothing, equally white knuckled and barely more stoical.

‘How high are we?’ I shouted.

Rodney shook his head. ‘High,’ he mouthed. Maybe he mouthed something else. He looked up, my eyes following his. The balloon was beginning to lose some of its shape, like it had been kicked on one side.

‘What did you say?’

‘We’re not out of this,’ he said. ‘The worst is still to come. Everyone hold the central column.’

Martin helped Sarah across the middle, both stumbling.

‘Rodney! What the hell is happening? Have you experienced anything like this before?’

He shook his head but then nodded. ‘Morocco.’ His attention was taken by the balloon again, the dent in the side even more pronounced. We never did find out what happened in Morocco.

And then, just as it was beginning to get difficult to breathe, we were out; out of the seething mass of cloud, catapulted into pale blue above. The high atmosphere, dazzling and translucent.

Like two cars chasing each other into a bend, momentarily our basket caught up with the lifeless balloon and then suddenly we were weightless. Weightless for a good few seconds. The basket tipped and we all hung in suspension, tethered to nothing.

‘Holy Christ,’ said Martin, ‘we’re in space.’

‘No,’ said Rodney. ‘It’s the top of the vortex. Hold on, all of you.’

And then, beyond the clouds, we fell. A huge pendulum that ripped and shanked as it plummeted earthwards. Everyone screamed. Me, everyone, and then we gripped on for our lives.

I knew we were all dead at that point. The basket swung and fell and the cables holding us to the balloon creaked and throbbed as they scythed against each other. Somehow keeping his composure, Rodney attempted a burst of gas, but swinging around so wildly, never directly below the limp balloon for more than a split second, it was completely futile. We fell towards Earth, still far below.

Rodney ordered us all to take off our shoes. Holding on, we obeyed. It was only when he threw his pair over the side, did I realise why. He grabbed a couple of our rucksacks, a camera case, a thermos and threw those over too.

‘What the hell’s the point?’ I shouted. ‘There’s no weight in any of it.’

‘The boy has to stay,’ Rodney yelled. ‘He’s got his whole life.’

‘No-one’s asking him to jump!’

‘We’re too heavy.’

‘Okay, okay,’ I shouted back. Around me were hollow faces and vertical hair. ‘We’re all going to get out of this fine. This is County Durham, for Christ’s sake!’

Martin spoke up. ‘I can’t jump.’

‘No one’s asking you to mate.’

‘I can’t jump,’ he repeated. ‘I’m the only one who knows the code for the grid.’

‘What grid?’ I shouted against the wind.

‘The electricity grid. When we have a blackout, I’m the only one who can bring the power back up. All the way to Carlisle.’

‘This is not the time Martin.’

‘We need Rodney to bring us down, so that leaves you three.’

‘Martin, we are not having this conversation. And anyway, why the hell should a bloody autistic electrician be any more indispensable than the rest? Come on!’

I could have also said a junior pathologist was at least his equal, except I felt a hearty slap across my back.

‘Fellas, fellas, please!’

It was the retired David. The first thing he had said in ages.

‘Sarah has to jump,’ said Martin. ‘Look at us, we’re too heavy, swinging like this. It’s got to be her. What’s she got to offer the world?’

It had only been a warning slap across my back. Rightly, David then punched Martin in the jaw, knocking him off his feet. Only his harness saved him from flipping out. I’m sure we all looked at it and thought the same thing, fleetingly.

‘Rodney,’ said David, ‘are we going to make it, all of us?’

‘No, the weight is too much. We can’t stay stable long enough to fire up the balloon.’

‘And would it save the rest, seriously, if one of us was to leave?’

David said ‘leave’ like it was stepping off a bus.

‘Maybe. Well, yes.’

‘You sure?’

‘Yes.’

The next moment will live with me forever. As the basket continued to swing and the air rushed around us, David unclipped his harness and sat back on the rim.

‘Hold my hand please,’ he said to me. I stepped across and took it. ‘Rodney…tell me when.’

He looked up at the limp balloon. I realised what he was thinking. He needed to time his departure just right. So that the pendulum swing would be reduced and we’d have the best chance of stability to fire the flame into the balloon. I opened my mouth to say something but David stopped me.

‘It’s okay. Really.’

When Rodney said ‘now’, David leaned out at the top of the swing. He unhooked my fingers and rolled backwards and away like a scuba diver from the edge of a boat. We continued to swing two or three times more, each time noticeably slower and suddenly hot air was shooting towards a small hole in the balloon and just beginning to find its way inside.

No one said anything. We all just looked from one to another. Martin started to speak but then we heard another sound. A sound far below that sounded like a scream. Actually, it was more like a euphoric roar. We all peered over the side.

Far, far below David was skydiving. Whether he had done it before, I didn’t know, but from where we were, his technique looked perfect. And he was roaring. From hundreds of feet above it was obvious that his cries were filled with adrenalin and pleasure.

I saw David again five days later. I hadn’t wanted to and promised myself I wouldn’t get involved, but when his sister came in to my department on the Thursday and asked for me specifically, I couldn’t say no.

I met her in the relative’s waiting room whilst the orderlies brought David’s body out from storage.

‘Thank you for meeting me. You were up there with him weren’t you?’

‘Yes, he was incredibly brave.’

‘But you understand now why he did it.’

I told her I did. My senior colleague had discovered the cancer whilst doing the autopsy. It was impossible to miss. It still didn’t lessen his courage however. She told me a bit about her brother. David had never married, living in Southern Africa most of his working life before being forced out by Robert Mugabe. Before she pulled back the sheet, she asked whether he was recognisable.

‘Yes, amazingly so. He managed to find a field with hay bales piled high and landed on his back. The impact killed him instantly of course, but his front remained almost unscarred. Remarkable.’

‘He was a great brother. I will miss him. He was keeping a list you know, one of those bucket things. Twenty things to do before you die. He didn’t show it to me but he would ring up after each new one was ticked off. Ballooning was number eighteen.’ She paused and fingered the corner of the sheet that covered him. ‘Shame he never got to finish it.’

I left her then, gave her the space she deserved. I waited outside and when she emerged a few minutes later, I hugged her before she left the building. I shed a few tears for the first time as I walked back along the corridors. Maybe they had been right. Maybe I had come back too soon.

Rachel, my senior colleague stopped me halfway.

‘John? Are you alright? Is the deceased’s sister still here?’

I shook my head. ‘Pity. We had a couple of effects to pass on. We’ll post them.’

I hadn’t realised. Rachel was holding a zip seal plastic bag. Inside was a smashed wristwatch and a crumpled sheet of paper. She opened the bag and passed me the contents.

On the paper, in impeccable handwriting, there was a numbered list of twenty things. It was untitled but by its nature, it was clear what it was. Number four: Read The Grapes of Wrath. Number twelve: Visit the cemetery at Ypres. Number eighteen: Ride a hot air balloon was unticked. I was tempted to do it myself, but then thought about his sister. It was a shame it was unfinished.

And then I looked again, at the remaining two.

‘Oh my goodness,’ I said.

‘What?’ said Rachel.

‘He did it. He finished the list!’ I looked up smiling. ‘Look. Number nineteen: Do a skydive. And number twenty: Donate my body to help someone else to live. He did it Rachel, he actually finished it.’

I ran back to the public area and out through the exit, managing to catch David’s sister just as her bus was arriving.

To ensure that you never miss a future issue of the print magazine, subscribe from just £24 for 4 issues.