THE TWAIN

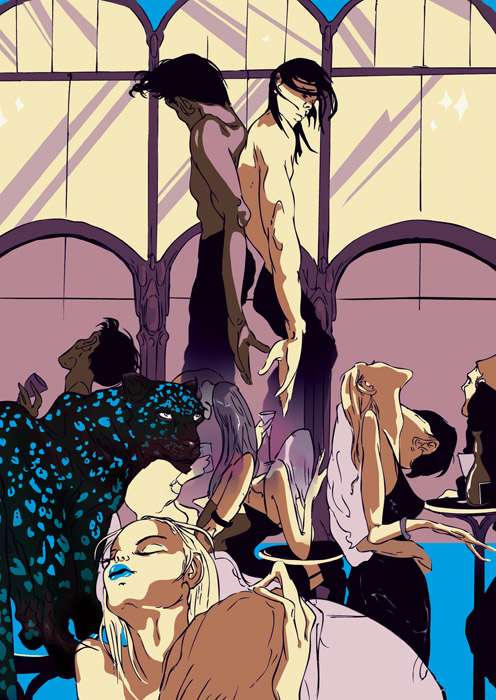

Set in Africa, Fabian Acker’s story details an idiosyncratic relationship between two men from differing cultures. Illustration by Ann-Christine Voss.

Walking so close that their hands were almost touching, Mark noticed that their shadows, long and soft now in the evening sun of Africa, were identical. Not all that unusual, he thought – a cat and dog might have identical shadows in the right circumstances. But the differences between the two young men were probably greater than between cat and dog. The least of which was that Sisay was black and Mark was white.

Sisay’s face had a touch of Somali; high angular cheekbones, a sharp nose and thin lips. Mark had a touch of the Welshman to him, not unlike Somali features; little flesh on the face, jet black hair, although long, where Sisay’s was tight and curly, and deep black eyes. It was a pleasure to see them smile; rare enough in itself, but when they smiled together it was like dawn breaking.

It’s satisfying, Mark thought, that we both have black shadows. Neither state nor society nor custom has demanded that white men have white shadows.

They had lodged for four or five years in adjoining rooms in a seedy hotel, normally only used by middle-ranking prostitutes, petty criminals or rich back-packers anxious to punish their parents. Neither Mark nor Sisay was known to have a permanent girlfriend, but occasional liaisons with prostitutes reassured the local community that they were not gay.

The black/white liaison was uneasily tolerated; the State was headed by a black president, the town administered by a black governor, and the law upheld by black police: equality was guaranteed by the constitution although ignored in practice, but the fault lines were mainly to do with wealth and poverty rather than black and white. A black/white friendship was just about acceptable across the race divide but only up to a point. The point was reached when a white man married his mistress; it was considered a betrayal by both sides.

The two men had met at the hotel, where Mark was staying after his parents had returned to England, waiting for them to send his ticket. The ticket never materialized and he found the kind of jobs that normally were available to well-born, ill-educated white men; clerking in the bank, helping out at the more elegant shops, or driving rich foreigners around the tourist areas.

Eventually, he found that he enjoyed carrying out the minor repairs on their hire cars far better than driving them; little conversation was needed, and the engines made no arch comment about a handsome white youngster without any commitments. He began to spend more time in the workshops repairing cars than driving them until he was skilled enough to make it a permanent job. The boss was pleased; drivers were common, competent mechanics were rare.

Sisay was staying at the same hotel as Mark because it was the cheapest place available that was safe. The town was populated by his tribe’s enemies who had collectively slaughtered the members of Sisay’s tribe in the bush — as his tribe had slaughtered theirs. He had washed up in the town on a tide of homeless youngsters. While the UN was there, there was a degree of safety, and they had put some of the refugees in the hotel to keep them out of the main town.

When the UN left, the killings flared up again, but on a reduced scale, and Sisay managed to persuade the manager to let him stay at the hotel in return for his washing up, waiting on tables and occasional repairs. He never went out, and welcomed the increasing demands placed on him by the manager as a way of killing time and staying alive.

After a year or two, when the situation was calmer, the manager lent Sisay to do some labouring jobs for a friend, the garage owner who employed Mark. There, Sisay also showed an aptitude for repair work and he eventually worked full-time as a mechanic, cultivating a friendship with Mark that had begun at the hotel but had been restricted by the guest/servant relationship.

When they worked on an engine together, they were like surgeon and anaesthetist. Unbolting the big end, refitting the tappets, or adjusting the timing belt, they would work with precision and rhythm, barely needing to talk to one another. Perhaps a better analogy might be a duet between a pianist and a violinist. A glance, a raised eyebrow or a sharp nod was enough to keep the two performances in perfect time, each contributing exactly the right amount of effort at exactly the right moment.

Although their friendship was entirely asexual, it was too strong to allow either of them to keep a girlfriend for more than a week or two. And as their tastes and backgrounds were so different, it would be impossible for them to share the same woman, although there were quite a few women in the town who might have welcomed the prospect of either or both. They were, after all, young, personable, and withdrawn enough to be mysterious.

While their friendship was apparently permanent, Mark was conscious of a growing rift between them. There were occasions when Sisay would return to the hotel just as dawn was breaking, smelling of vomit and beer and sometimes with bruises or dried blood on his face and arms. In the dark regions of the town, where white men couldn’t or didn’t go, Sisay would try to forget his bonds to Mark; loving and hating him simultaneously, he would resolve his conflicts in violence or drink or sex.

Sisay also had to cope with the more immediate tension. News of inter-tribal massacres would drive him in to himself, and his conversation, laconic at the best of times would dry up. After work, he would leave Mark to eat his meal alone, and he would go off to tread his own lonely path. But these edgy episodes were forgotten on certain rare evenings, when, for an hour or two, when the African night was calm, they would become perfect partners in a strange duet.

On these occasions, when they had gone to their rooms after a day’s work that had gone well, and after an evening meal marked by quiet harmony, they would meet a few hours later on their joint balcony. Standing naked side by side on the balustrade, neither looking at each other nor speaking, they would each stretch out their arms like men anticipating the Cross.

Then, with their fingertips just touching, they would float gently off across the sleeping town, swooping, soaring, wheeling like falcons or hovering like kites, fluttering like death above the streets. Sometimes they would skirt the edges of the forest and see a jaguar padding purposefully along a twisted path. Or sometimes, on the edges of the black township, see two lovers hugging the shadows, hurrying towards a clandestine meeting.

Without talking or even glancing at each other they would hover above the squalid one-room brothels and the ragged-roofed huts, where beer and palm wine were sold. Laughter, shouts and sometime sweet music would float upwards towards the two friends, and as dawn started to break, they could see the men and women leaving for home, swaggering or stumbling on the same paths that Sisay sometimes used.

The days after a flight were difficult for both men. Sisay would go on three or four binges in succession, leaving Mark as distressed as a mother worrying over a sick child. And their working rhythm would suffer. Probably not enough to be noticed by an outsider, but both would feel anxious and disjointed. They never spoke about Sisay’s defections, nor the disjointed tempo of their work, nor for that matter about their flying — but each knew that the other was not at ease.

Sisay took to his solitary pursuits more often as the news of tribal conflicts became more frequent, and Mark would increasingly think about flying, longing for the calm affection that would accompany them above the town. But it could only follow an evening of comradeship that was generated by a day of successful work. It could only happen spontaneously, and without any conscious effort.

One night, despite the feeling that the conditions were not right, he stood on the balustrade, willing Sisay to join him. He stood for many minutes with his arms outstretched, eyes closed until he suddenly felt the swift pleasure of Sisay’s fingertips touching his. His soul lifted, and the pain of the last few weeks dissolved. Leaning confidently into the warm night air, he plummeted like a falling angel.

It took months for him to recover, even though he was flown to the capital to a ‘proper white’ hospital. But he was young, the bones knitted, and the ruptured liver healed.

He went back home, first to the garage to ask about Sisay. His former boss was pleased to see him. ‘Sisay? I don’t know who you mean kid. There was only one other mechanic apart from you. Pierre – you remember him don’t you? He’s gone home to Belgium. There’s Olu there,’ he gestured, ‘but he doesn’t count. He doesn’t know a spanner from a horse’s arse.’ Olu, hearing his name, smiled obligingly. ‘You can have your job back as soon as you’re ready, son,’ he smiled. ‘Lots of customers have been asking for you. In fact…’

He stopped talking. Mark had already turned away and was hobbling on his crutches back to the hotel.

The manager had changed since his accident. No longer the deathly thin ex-Legionnaire wearing tattered khaki shirt and trousers with a cough that could be heard throughout the hotel, but a smart white young man, dressed in tidy shorts and a crisp white shirt with matching teeth. Unlike his predecessor, whose characteristics of despair, indifference and contempt were immediately visible like the flakes of dandruff in his beard, the new one was tight, bright and brisk.

‘And you are?’ he said smiling tautly, as Mark leaned his crutches against the reception desk.

‘I live here. Room 15. Next to Sisay Kazibwe. Room 16. Been here nearly five years.’

‘Well I don’t think I can help.’ He smiled again, with the cheerful warmth of a cobra. ‘We don’t have a Room 15. They have names now, not numbers. New York, London, Moscow, Paris, each themed according to its name – so I’m not even sure what room you mean. But in any case we’re fully occupied, and, since I’ve taken over,’ he lowered his voice, ‘we let our rooms to exclusively, well, lighter-coloured clients. So I don’t think your friend would find it comfortable here, even if we had a vacancy.’

Mark was too engrossed in his search for Sisay to feel the arrogance and hostility. ‘Do you know if Mr Kazibwe left a forwarding address?’ He felt dry and anxious. He already feared what the answer would be.

Mark glanced at the barely familiar reception area, with its now mahogany floor and crisp pictures of impossibly beautiful views of Africa. The tatty ‘Joyeux Noel’ banner which had been hanging from the ceiling year in, year out since he had been there had gone, and there were hundreds of tiny mirror tiles where once the plaster had bulged and crumbled.

He looked up at them behind the reception desk and his heart leapt. He saw Sisay’s fractured reflection smiling at him, and turned around quickly.

Nothing.

Nothing.

To ensure that you never miss a future issue of the print magazine, subscribe from just £24 for 4 issues.