TALBOT

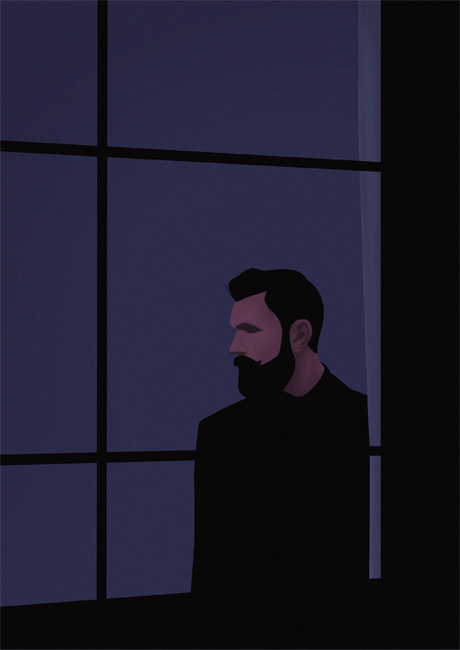

A lifelong friend is discovered to have a plethora of horrific secrets in Adena Graham’s macabre short story. Illustration by Thomas Danthony.

Ever since I’d known Talbot, he insisted he had been raised by wolves. Of course, I never really believed him. Until now, as I sit in the public gallery, watching his almost inhuman stillness as he stares unblinkingly through toughened Plexiglas while the charges are read out.

Whilst many would argue that wolves are feral creatures, capable of extreme violence, none have ever been accused of keeping a severed head in their fridge. It was a head – that of a woman in her late twenties – which finally gave away the extent of Talbot’s savagery, rather than any lupine faux pas, such as ordering raw meat in restaurants or rummaging through bins.

Indeed, had the head never been found, I would have continued to view Talbot as an affable, if slightly unconventional, sort of a chap. All of this has now made me doubt my judgement. I’ve always considered myself to be good at reading people, but I had actually sat with Talbot, putting the world to rights over a tumbler of Glenlivet, while a head nestled between a wedge of Stilton and a bunch of grapes inside his fridge.

I first became friendly with Talbot in our final year at university. Indeed, I’ve known him for a long time: a fact that always causes raised eyebrows amongst people who assume I must have known he had a fondness for storing body parts. If only I did.

When we met, he was bearded and cut a rather dishevelled figure. I wasn’t sure whether he had cultivated the beard to give credence to his story about being dragged up by wolves or if the beard came first and then the story popped into his head. Either way, while most of us laughed at him, both to his face and behind his back, he persisted with this tall tale and at times, when he was at his most unkempt, I could almost believe it.

Looking back, this idiosyncrasy was probably the first seed of Talbot’s ripening insanity. After all, most young men don’t go around claiming to have hunted in a pack at the age of six, or to have suckled from the teat of a grey she-wolf. But would I have said then, or over the subsequent years, that he was the type to do what he later did? Certainly not. He was odd, no doubt about that, but odd and evil are worlds apart, supposedly.

There was one thing, though, that did give me pause for thought. This would have been when we were in our early thirties. All of us, except for Talbot, were married by then with children of varying ages. However, his singleness had always been something of a taboo subject. In all of the time that I had known him, he had never spoken of dating anyone, or even having a fling with a woman, or man. He was, if you’ll excuse the pun, something of a lone wolf. However, true wolves tend to gather in packs and it was this enforced solitude, more than anything else, that made his story seem far-fetched.

Interestingly, he was still rambling on about having been reared with these animals even then, a decade after we had first met. I wouldn’t say it was a frequent topic of conversation, but it did crop up with surprising regularity. For example, you might tell him about something your child had done, and he would say, ‘If I had done something like that, I would have been given a sharp nip on the back of the neck.’ I would always wait to see the glimmer of humour in his eyes – something to say that he was finally ready to admit this had all been one long joke – but it never happened. He would always regard you levelly, seriously, as if challenging you to snigger or call him out on it.

Anyway, this incident was one of the only things that made me wonder if Talbot was simply eccentric or whether there was something truly dark lurking inside him. As I said, raising the issue of his single status was something of a no-no. We had learned over the years not to try and push him on the subject, not because he reacted in a violent or angry manner, simply because it was the one topic that guaranteed to make Talbot clam up.

The university bunch had tried to set him up on a blind date in the early days and we didn’t see or hear from him for two weeks after that. He froze us out as though we had never existed. Then, one day, he just turned up again and no more was said about it. After that, nobody pushed the issue again. Other than the wolf thing, he was actually pleasant company, entirely agreeable to be around, and none of us wanted to upset him.

About twenty years ago, a little more than a decade after Talbot and I had met, my wife Marion arranged a dinner party. She has always been good at organising things, so I just gave her the name of a few friends and their wives, and she got on with it.

On the night, I was surprised when Talbot showed up. I hadn’t asked her to include him because a dinner party is generally something that you invite other couples to, and I wouldn’t have subjected Talbot to sitting there like a gooseberry. Nonetheless, I offered him a warm welcome and hid my surprise well enough. It was only when the next guest to walk through the door happened to be a recently divorced friend of Marion’s that the alarm bells went off.

I cornered my wife in the kitchen and asked her what she was playing at. She giggled mischievously. ‘Poor old Talbot’s always alone,’ she said, ‘and Lucy’s been really down since she and Tom split, so I thought I would try to subtly set them up.’ I blanched at that. I had never explained to Marion why none of us interfered with the wolf-man’s love life, and I had never considered the possibility that she would try to play Cupid. ‘This is a disaster’ I had hissed, but at that point Lucy, the divorcee, had sidled into the kitchen and I had been forced to take my leave.

To say that the tension was palpable when Talbot was directed to sit next to Lucy is an understatement. I genuinely thought he was going to refuse to take his seat. He just stood there, gripping the back of the chair, while his knuckles turned white.

Eventually he did sit, but not before casting my wife an utterly hateful stare. She didn’t notice, as she was already heading towards the kitchen to round up the first course, but I certainly did. Even now, I can recall the sinking sensation in my stomach and the chill that flitted through me. Here was a man I had known for years, someone whom I trusted, eccentric though he might be, but that look he threw my wife was one of pure loathing.

Talbot barely spoke during the meal and the atmosphere in the room grew increasingly uncomfortable. If my old friend was aware of this, he either didn’t show it or didn’t care. There was one more thing during that abominable dinner party that made me suspect I was in the company of someone who had a far darker side than I had ever imagined, and that was when my wife presented the main course of steak au poivre. Perhaps, had Talbot torn into it with his bare hands – as might befit a man who claimed to have been raised by wolves – I would have found it less alarming than the furious way he attacked it with knife and fork, hacking at it until it looked like my wife had served up mince.

After that dinner party, I didn’t see Talbot again for a few years. It’s not that anything was said or that we fell out, we just quietly parted ways. There are some people, however, who are destined to remain in your life, and we eventually bumped into one another in a London wine bar. Enough time had passed for me to have forgiven, or at least justified, Talbot’s behaviour at the dinner party. What had seemed sinister at the time, I now put down to extreme discomfort on his part. After all, being paired off had always been one of his phobias.

And so our friendship resumed and the years ambled by, as they do, with nothing to indicate that there was anything more amiss with him than being a confirmed bachelor who still insisted he had been brought up in a pack.

Now, as I sit in court, listening to Talbot’s guilty plea, I wonder if his youthful reluctance to be set up was some attempt on his part to contain a wildness, which even then he knew was spreading through him. Did he seek solitude for fear of what he would do to a female, should he ever find himself alone with her? That head was just the tip of the iceberg. What they found buried in Talbot’s cellar, beneath his garden, behind the garage brickwork, was the result of decades of dedication. How many times must I have popped round for a pint and a chat over the years, unaware of the dark secrets that lurked in Talbot’s heart and behind his walls?

At first I am confused, furious, betrayed, disgusted, hurt, shocked, as the prosecutor reads out the details of the offences. I don’t think there is an emotion that doesn’t hit me as I sit rigidly on the hard bench of the public gallery. And then Talbot’s defence counsel begins his mitigation and reality takes a subtle shift. What a childhood he had! Privileged beyond imagination; holidays in exotic locations, riding lessons, fencing lessons, designer clothing, but all of it hiding the most terrible abuse imaginable.

Inside the six-bedroom house where he lived, there was a space reserved for him – but not inside the blue and white bedroom adorned with toy soldiers, games, books, and puzzles. No, that was all for show. Talbot’s life was spent in a small cupboard under the stairs. He was fed scraps, burned with cigar butts, forced into cold baths and more, so much more.

There is a silence in court when the barrister has finished. Maybe the shock is greater because you don’t expect to hear about that sort of abuse happening in upper-class, wealthy households.

Now, suddenly, I understand. The enigma of Talbot has been fully revealed to me. He escaped, finally taken into care when he was twelve and once free, created an alternate reality for himself. A family of wolves whom, wild and untamed though they were, couldn’t have been any worse than the hand he had been dealt. After all, when humans have let you down, what else is there to turn to?

In fact, I now understand that Talbot would have fared better had he truly been raised by a pack. He would have been looked after, protected, shown right from wrong. He would have been blessed with a mother who would have fought for him, tooth and claw, rather than handing him over to a man who waited with a burning cigar and an unfastened belt.

Talbot had lived through most of his childhood in a wasteland of neglect and abuse. Humans had shown him no kindness, nor taught him any kind of moral code. When, eventually, he was forced out into the real world, he brought his feral beginnings with him. Sadly, for the many women he encountered over the years, these weren’t the values of the pack, as he had always claimed, but that cold absence which sometimes arises in earth’s most dangerous of animals: man.

As Talbot is led away to the cells to end his days as they began, in confinement, he pauses. Glancing back over his shoulder, his eyes meet mine. I finally see in them a pain which he has kept hidden all these years, and I nod a silent goodbye to the man who never really belonged.

Throwing back his head, he releases a blood-curdling howl. It echoes throughout the courtroom and bounces off the wood-panelled walls, filling every corner of this large space. At that moment, I realise that for all his claims of being reared by wolves, this is the first time I’ve ever heard Talbot howl. In reality, he had been howling all along.

To ensure that you never miss a future issue of the print magazine, subscribe from just £24 for 4 issues.