KEVIN JARED HOSEIN: ‘I’M NEVER BORED BECAUSE I’M ALWAYS TRYING TO FORM AND FIX STORIES IN MY HEAD’

The Repenters author talks to Popshot editor Matilda Battersby about his first novel for adults.

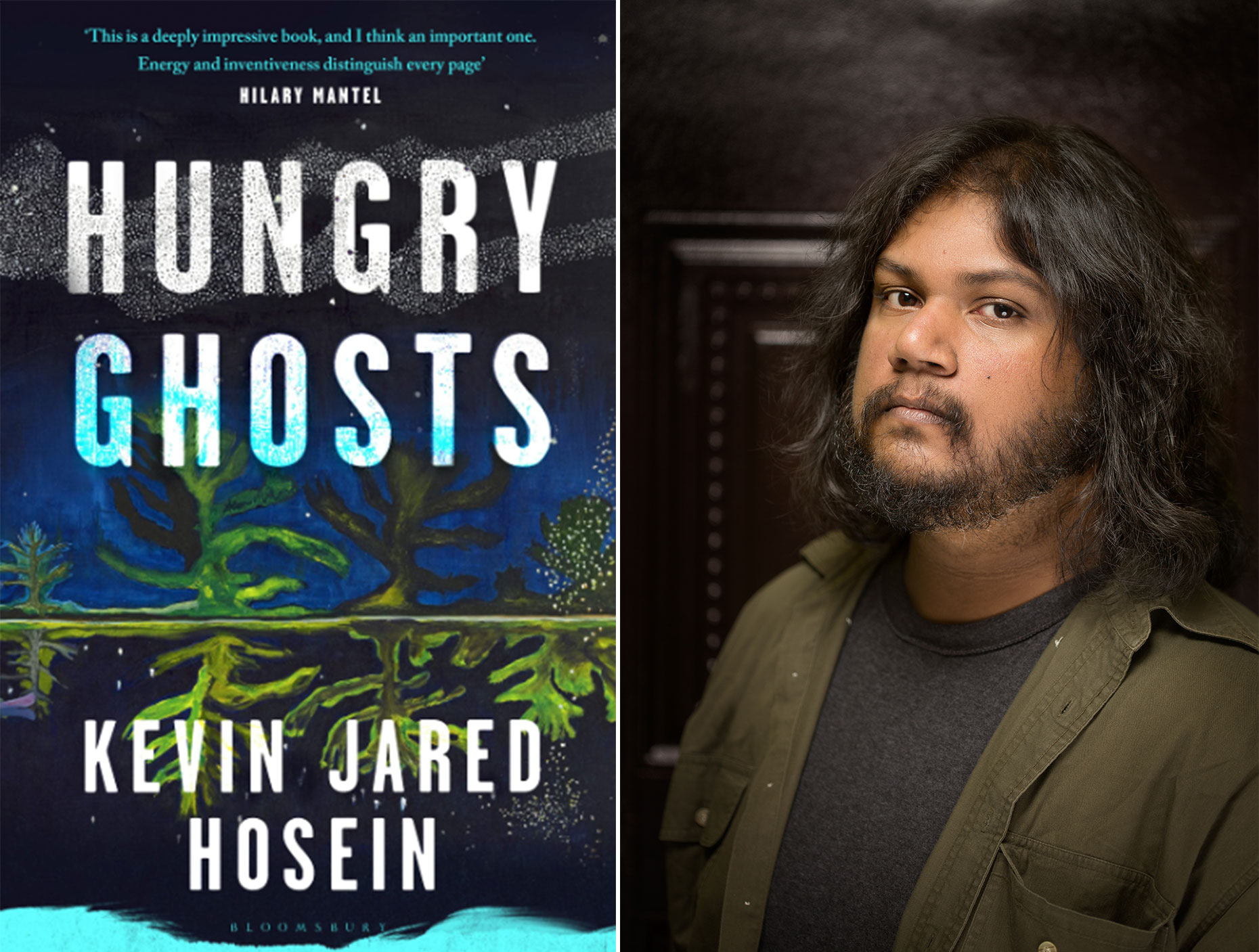

Kevin Jared Hosein, 37, is an award-winning Caribbean short story writer, poet and novelist who worked as a secondary school Biology teacher for over a decade.

In 2018 he won the Commonwealth Short Story Prize. He has published two books for Young Adults, The Repenters and The Beast of Kukuyo, both of which were longlisted for the International Dublin Literary Award.

An extract of his first novel for adults, Hungry Ghosts (Bloomsbury, £15.29), appears in the Heart Issue of Popshot Quarterly.

Q. Thank you so much for being our guest author and contributing an extract of Hungry Ghosts. Can you give us some insight into how the idea for this novel took root?

A. A few years ago, I was commissioned by the Commonwealth Writers group to pen an article about Trinidad and Tobago, mainly focused on culture or history, or something untold. I had often visited the village I grew up in, listening to stories told by my family, especially my aunts and grandfather. So, I decided to interview them. A story that popped up was that of an aristocratic woman who had visited their street back in the 1940s or so. She had tripped on a chuckhole and landed in some mud, prompting some villagers to laugh at her. Her intended revenge was to have the village demolished, which didn’t happen in the end. That incident was only a footnote in my article, but as I ruminated on it, a character and concept came to life in my mind. So Marlee Changoor from the novel was the trunk, all other characters branching off from her. My mind’s image of the aristocratic woman in her elegant but muddied white dress became one of the central images I came back to, chapter to chapter.

Q. Can you please explain a little about the role of the landscape of Trinidad in your novel. It’s so vivid it feels like another character in the story

A. There’s a short story by Jack London, All Gold Canyon, that focuses on a violent skirmish between a gold miner and a bandit. The story opens with lush descriptions of the river, the air, the trees. After all is done (and blood has been shed), the story simply ends with another description of the wind and greenery, as if the life-and-death battle between the two men had just been a brief interruption in otherwise another epic taking place in the background. Eventually, bodies decompose, voices fade with the breeze, odours blend with mud. I think of the Trinidadian landscape in such a manner—simultaneously beautiful and uncaring. The fields will flood; the ibises will roost; the corbeau will feast. Altogether, because the novel has a roving spotlight on a number of characters, I saw the verdant and inconsiderate landscape as the fixed point, as if we could inhabit the animals and trees observing these humans of the land.

Q. What’s your writing process like?

A. Because I had been working a full-time teaching job, writing was mostly done on weekends. There’s no stringent routine — I jot down notes sometimes when I had free time between classes or while waiting in line at the bank. I’m never bored because I’m always trying to form and fix stories in my head. Always going down alternate roads with each character and see how they react. I do have a desk that I do my ‘heavy’ writing on, but I like to re-read and edit while in bed. I keep books nearby that I believe match the mood of the stories I’m trying to write. This one, there was some Faulkner in there, as well as Yukio Mishima and Annie Proulx.

Q. Can you tell us a bit about your poetry and how you work out which form a creative idea is going to take?

A. My poetry isn’t something I’m often asked about, because I rarely put it out there. I’ve read some poems on stage and have very few published, but I do enjoy reading and writing poetry even though half the time I feel like I’m lost — though that’s not a bad thing! A lot of it ends up osmosing into my prose. Whenever plotting scenes, strange ideas I’d had while reading or writing a poem may come to mind. Two characters are in a quarrel in a closed room. I may imagine the world of that room tilted 15 degrees diagonally from the character’s POV and re-write the scene to reflect that notion. Or a mentally submerging a character in an underwater tunnel filled with electric jellyfish as they nervously visit a new and frightening place. As I said, it’s a series of strange ideas that never quite make it to the page. In short, it’s fun to write poetry because it makes you discover the uncommon in the common — things you never knew your mind could form.

Q. How has your background as a science teacher influenced your writing?

A. One gripe my Biology students have always had was that there were simply too many words to learn, whether that be a word like ‘megasporangium’ or ‘allantois’. They are all specific and necessary and form the foundation of building the bigger picture of understanding the life processes. Some readers may become irked by my inclusion of scientific language in my descriptions (flabellate, arcuate, abscissa, sclerotic), though I think of them as beautiful and poetic when placed outside of their specific contexts and circumstances. I do have to learn to hold back, I admit.

As for the job itself, I had to constantly find things that would interest my students, from the miraculous to the utterly bizarre. There are a lot of ideas I’ve picked up along the periphery when reading articles or books about science, especially those about animal behaviours and epidemiology, both the physiological and social aspects of it. It has exposed me to many concepts and hypotheses that I probably would not have explored if I hadn’t been working in the field.

Read an extract from Hungry Ghosts in the Heart Issue of Popshot Quarterly.

To ensure that you never miss a future issue of the print magazine, subscribe from just £24 for 4 issues.