THE LEAVING PARTY

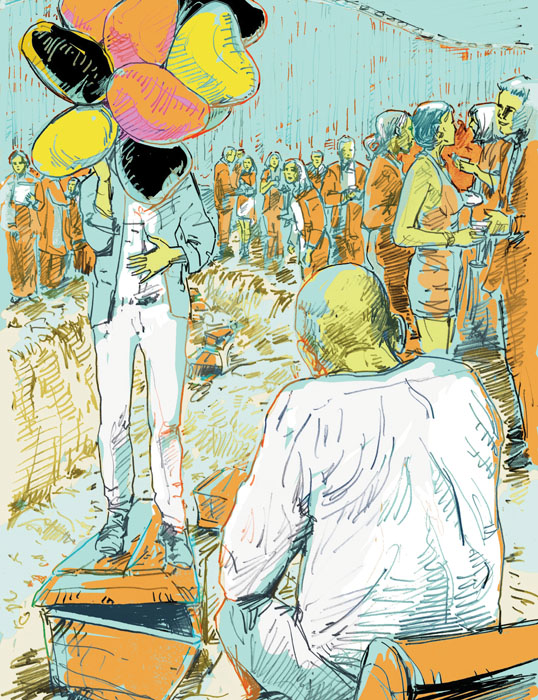

Ruth Bennett’s short story dips into the life of a government employee who approves a scheme that eventually comes back to bite him. Illustration by Roland Hildel.

Alfie Mellor had spent most of his life thinking about time. About how it expanded and contracted, like a muscle. How it bent to your will or resisted. How time stretched ahead, the horizon always shifting further away. At least that was how it used to be. Before.

He took a sip of water. It should have been a simple action, but these days everything needed breaking down into several steps. First he lifted the glass. His hand shook slightly, but the glass was almost empty, so it didn’t spill. Then he brought it to his mouth and licked his lips to stop it sticking. The water trickled over his tongue and down his throat.

The creak of a plastic chair brought him back to the present. He set the glass down and looked around. Most people were familiar and he supposed that those who weren’t probably should be. They were looking at him expectantly. He dropped his eyes to the armrest of his chair. His chair, in his house. The chair hadn’t always been covered in this fabric, but he couldn’t quite picture the original. It hovered just out of reach, like so many things. Finally, his mind settled on what he’d been planning to say.

‘You might think things were different back then…and make no mistake, they were. But people are people and that never changes. All of you, you’re the future. I’ve made my choices and I’ve lived with them, but I’ve never actually told anyone about what happened on that day. The day when everything changed for me.’ As he spoke, Alfie stopped seeing the faces before him.

When I get to the café, the light’s already fading. It’s one of those days where it never feels like the sun fully rises, but the café lighting pushes away the blunt-steel grey of the outside. I spot Oliver, the party planner, sitting at a table, tapping his order into the service pad. He’s taken off his coat, so I can see he’s in a smart navy suit and white shirt. I think I’ve made good choices; my shirt is white, like his, and my suit is an inoffensive grey. Don’t wear black, whatever you do, he’d said. It doesn’t fit with our message.

‘Hello, Oliver,’ I say. ‘Thank you for agreeing to let me –’

He cuts me off with a wave of his hand. ‘Right, Alfie, when we’re at the house, we should be as inconspicuous as possible. This is someone’s leaving party and it’s all about them. And the nearest and dearest, of course. Don’t engage in conversation with any of the guests.’ At this point he fixes me with a stare. ‘Robert Cripps is the name of the birthday boy. You’ve read through the profile, the running order and the protocol documents?’

I nod. ‘Yes, although I do have a couple of questions.’

I’d spent last night writing a whole list of things I wanted to ask. This report was my chance to really impress my manager. I’d been dropping hints for months about how much I wanted to work on the advisory team and he’d finally given me a break.

‘Go ahead,’ Oliver replies, looking at the time on the wall and pressing the service button.

I skip over my first two questions. ‘What if, in the end…I mean, when it’s time…what if he doesn’t want to, well, leave?’

Oliver leans back. ‘Don’t worry about that. They never do, not when it comes to it.’

‘The official guidelines state that briefing the subject and the family in advance will avoid resistance during the –’

‘I know what the official guidelines state,’ he says. ‘But you don’t know anything until you’ve seen it for yourself…’

‘And that’s why I’m here.’ I won’t let myself be intimidated. I’d been told to expect this. Apparently it’s common for front-line staff to inflate their own importance.

Go take a look, my manager had said. But observing the event is just one part of the process for compiling your report on the trial scheme. You know how much work it’s taken to get us this close to national approval. I can count on you, Alfie, can’t I?

I realise that Oliver is speaking and I shift my focus.

‘…Anyway, just follow my lead.’

In my mind, I run through my research. The statistics are compelling. Overpopulation, misdirection of stretched healthcare resources, improper distribution of wealth.

A waitress appears carrying two coffees.

‘Drink it, and let’s go,’ Oliver says. I swig it down, even though I don’t drink coffee.

Oliver scans us into the house using guest passes, and the door slides shut behind us, cutting off the drone of the wind. We squeeze past a group of people clustered in the hallway, chatting about their jobs and home-improvement projects. An attendant takes our coats and I get a chance to look around. Technology is noticeable by its absence. Beyond the wall screens and the home-management pads at the doorways, the house wouldn’t look out of place in a film set 20 or 30 years ago. The shelves are filled with books, and vases of flowers vie for space with ornaments and trinkets.

We enter a large room where more people are gathered. Most are standing, apart from a couple of elderly ladies who are sitting on a sofa that’s been pushed up against the wall. They’re dwarfed by the sagging cushions as they stare up at the family photos on display. Their blinks when the image changes are the only sign they’re actually conscious. In the centre of the room are a couple of trestle tables covered in a buffet spread and decked out with colourful balloons. A waitress is carrying a tray filled with glasses of wine. She nearly drops it when a gentleman steps backwards, accidentally bopping a bright ‘100!’ balloon into her path. I don’t realise I’m staring until Oliver clears his throat and cocks his head to one side, drawing me over to the corner of the room.

‘This is good,’ he says. ‘A nice, relaxed feel – very authentic, which is good. Good,’ he repeats. ‘I need to locate the family and authorise the wording for the speech.’ His eyes flick to the time on the nearest screen. ‘We’ll have the goodbye ceremony at 4 p.m. We’ve only got the birthday boy speaking today. There isn’t a surviving spouse, which makes it easier. And the children tend to be pretty relaxed, if you know what I mean…’ He raises his eyebrows, which makes me shiver involuntarily. ‘We should be done and dusted by seven. Any questions?’ I shake my head. ‘Help yourself to some food, soak up the atmosphere. I’ll need you up front with me during the speech, ready for the final departure.’

I walk over to the buffet and transfer some food on to a small plate. I know I won’t actually eat, so it doesn’t matter that the mayonnaise in the pasta salad has already begun to congeal. I pick at the food with a disposable fork and focus on the conversations around me.

‘It’ll be my mother’s leaving party in a few weeks.’ A woman who I guess to be in her seventies is speaking. Her hair is carefully arranged and there are signs of Botox around her eyes. ‘She doesn’t have much idea what’s going on from one day to the next, thank goodness. Not like Robert. I mean, he was lecturing up until recently. Such a shame…’

‘You’ve got to think of the young ones, though, don’t you?’ another woman adds. ‘I know my Kacey is grateful. She’s been on the housing list for 16 years! Things have finally started moving since the scheme was opened up to our area. Surely that’s a good thing?’

To my right, two teenage girls are speaking.

‘What are you doing?’ one hisses.

‘Shh!’ the other replies. ‘What’s your problem! Gramps knew how much I liked this.’

‘Gramps knows, you mean. I can’t believe you’re talking like that already!’

I risk a sideways glance and notice one of the girls tucking an ornament into her handbag.

‘He always said he’d give it me.’

‘Then he’ll have promised it you, won’t he? I can’t believe you’re not even gonna wait until they give the stuff out.’ The girl sighs and shifts her weight, seeming to remember they’re in public. I turn away quickly. ‘Anyway,’ she continues, ‘have you even been to see him yet?’

I look around, searching for the event I’m so familiar with on paper. If you’d have asked me a week earlier, I would have called myself a policy specialist but now I’m here, it’s clear I don’t know half as much as I thought. A migraine is building in the centre of my forehead and my mouth is dry. My brain feels like it’s been shrivelled by the coffee. I think about going outside, then I realise I haven’t got a pass. In any case, I can see the sky welling up with clouds, threatening to spill. I edge my way through the guests and into the hallway without making eye contact. It’s quieter there and I feel the panic subside, but I’m still far from calm and I desperately need water.

The kitchen is the first door I try — across the hallway, past the people who have moved on from redecoration projects to holidays. I head straight to the sink and take a mug that has been left upturned on the draining board. I wave my hand under the sensor and catch the stream of chilled water that jets out. As I gulp it down, I can feel the water expanding the cells of my brain but the migraine doesn’t shift. I screw up my eyes and press my temples.

‘I thought it was just me who was finding this whole thing completely fucked up.’

I turn sharply to see a woman about my age sitting at the kitchen table. Despite the tough edge to her voice, she looks fragile. Her eyes are red-rimmed and she’s rubbing at her knuckles.

I have no idea how to respond, but then she speaks again. ‘I don’t think we’ve met. How do you know my grandfather?’

Before I even think, the lies are spilling out. I’m remembering details from the profile that I didn’t realise I knew. I tell her how much I admire her grandfather’s art. How I studied under him at university. How I think his use of accelerated biodegradable materials has far-reaching implications for the future of the contemporary art scene. I don’t know where this stuff is coming from, but I even start to believe what I’m saying.

‘You’re so right,’ she says. ‘He’s the most alive person I know. I guess that won’t be lost if people like you remember him. Not like all of them.’ She nods her head at the closed kitchen door. ‘I don’t know how they can just end something like this,’ she says. ‘For them it’s just a numbers game. Surely this isn’t the answer? And what about when it’s our turn? What if they change it to 65 for us, or 50? What if they decide tomorrow that I don’t fit their vision of the future?’

I don’t know what to say. I want to share in her disgust. I want to forget who I am.

‘What’s your name?’ I ask. The mundanity of the question seems absurd, but I want to know. As I speak, the kitchen door slides open and Oliver walks in.

‘There you are, Alfie. I’ve been looking for you. We’re going to be behind schedule at this…’ He trails off. It’s almost comical the way he looks from me to her and back to me.

All I can think is that I don’t care about Oliver, I don’t care that I’ve been caught acting against the guidelines. I care about the fact I’ve been outed as one of ‘them’ in front of this woman I’ve only just met. If I really thought we were doing the right thing, why hadn’t I told her so? But I know why. I’d been kidding myself this whole time. Kidding myself that we’d created a civilised solution. Kidding myself that this wasn’t yet another case of the government manipulating facts to fit their agenda.

Somehow, I manage to coordinate my feet so they follow Oliver out of the kitchen. I know she must be watching me, but I don’t look back.

It’s almost completely dark outside now and the windows have become like mirrors, reflecting endless versions of us all, wrapped up in artificial light. The trestle tables have been cleared away and in their place is a single armchair with a microphone on a stand just in front. The rest of the room is taken up with rows of plastic chairs facing the armchair, split into two sections by an aisle. Every chair is taken. I stand at the front. Next to me, in the armchair, is Robert Cripps, the birthday boy. On his other side, Oliver.

The old man begins to speak. He doesn’t even glance at the paper in his lap and his voice is clear and strong. There’s no real need for the microphone. As he thanks everyone for coming, I search the crowd, but I can’t see her. The ceremony is the part I thought I’d appreciate most, but I can’t take in anything Robert’s saying. His granddaughter’s words circle round my mind. They don’t care about who he is.

Then Oliver begins speaking. ‘Thank you, Robert. And now, everybody, it’s time to sing.’

People are stirring in their chairs, looking at one another and whispering. Robert is still speaking, but Oliver has taken the microphone and is singing the opening lines of ‘Happy Birthday’. The catering staff are singing too and gradually the guests join in. Oliver is trying to catch my eye as he sings and eventually I understand what his look means. It’s time. Together, we hook our hands under Robert’s arms, lifting him up to standing. He resists, planting his hands firmly on the armrests, but there are two of us. Once he’s upright, we begin to walk down the aisle, the old man between us. Once we get him out of the room, we start the clumsy journey upstairs.

I’ve been concentrating so hard on not tripping that I haven’t heard what Robert is saying. But now we’re away from the crowd, I listen.

‘The future will judge you,’ he says, over and over. ‘The future will judge you.’

When we reach the bedroom, he wriggles his arms and strains against my grip.

‘Have you got him?’ Oliver checks, then releases his hold and retrieves a small black case from his jacket pocket.

He withdraws a small jet-injector, presses it against Robert’s arm and pushes down. I gasp instinctively, thinking that’s the final shot, then remember it’s just a sedative. It works instantly. We dump him on the bed, then set about arranging him for the family. Oliver looks around at the balloons, the photos, the flowers. ‘All this effort to make it nice,’ he says, shaking his head, ‘and most of the time it’s a waste. He’s not even conscious.’ He pauses, then adds, ‘I’m not going to ask you what that little scene in the kitchen was about.’

‘Don’t worry,’ I say, busying my hands by smoothing the wrinkles from the bedspread. ‘She did most of the talking.’

The woman from the kitchen is the last in a stream of grandchildren. As she enters and sits by her grandfather, she looks only at him. She strokes his hand and murmurs words none of us can hear, then stands abruptly and makes for the door. As she steps out on to the landing, she turns and stares right at me. I see the judgment in her eyes.

Alfie Mellor finished speaking and blinked, taking a second or two to process where he was. So many years had passed, but he could remember every detail of that day. And now it was his house, his family.

‘But you approved the leaving party scheme? You must have done…’ It was Joseph, his grandson. The one who looked too much like the person he used to see in the mirror.

‘That’s right. My report was part of the bill.’ He hesitated. ‘It wasn’t what I wanted. The first version of my report advised against the scheme, but it was rejected. I was given the opportunity to revise it and keep my job, so I did. I wanted to get on, you see. And I did.’

‘It’s time,’ said a quiet voice behind him.

Alfie didn’t turn to see who spoke. He simply closed his eyes as everyone began to sing.

‘Happy birthday to you…’

To ensure that you never miss a future issue of the print magazine, subscribe from just £24 for 4 issues.